Launched by The Nippon Foundation and designed by 16 leading Japanese architects and designers, The Tokyo Toilet project is a combination of Japan’s extraordinary standard of hygiene with unique design features.

Text: Witinan Watanasap

Photo Courtesy of Satoshi Nagare, Courtesy: The Nippon Foundation, SS Co., Ltd. Hojo Hiroko. except as noted

Photo Courtesy of Satoshi Nagare and The Nippon Foundation

ความสะอาดและสุขอนามัยนั้นเป็นสิ่งพื้นฐานที่ทุกเมืองให้ความสำคัญมากขึ้นและพัฒนาเพื่อให้เกิดความเป็นอยู่ที่ดีของประชาชน สำหรับประเทศญี่ปุ่นมักจะได้รับการยกย่องเรื่องความสะอาดเป็นประเทศอันดับต้นๆ ของโลก แต่ก็มีชาวญี่ปุ่นจำนวนไม่น้อยที่ยังคงไม่พอใจ ต่อห้องน้ำสาธารณะของประเทศตัวเอง ที่มักจะมืด สกปรก และเป็นแหล่งมั่วสุม จนทำให้คนส่วนมากไม่กล้าที่จะใช้งาน จากปัญหาดังกล่าว มูลนิธินิปปอนจึงได้ริเริ่มความร่วมมือกับที่ว่าการเมืองชิบูย่าและสมาคมท่องเที่ยวชิบูย่าดำเนินงานออกแบบ ‘โครงการห้องน้ำสาธารณะโตเกียว’ ขึ้น เพื่อยกระดับสุขอนามัยให้แก่ชาวโตเกียวด้วยสิ่งอำนวยความสะดวกที่ครบครัน ด้วยการสร้างห้องน้ำสาธารณะใหม่ จำนวน 17 แห่ง ร่วมกับนักออกแบบและสถาปนิกที่มีชื่อเสียงของญี่ปุ่นในพื้นที่ต่างๆ ในย่านชิบูย่า ซึ่งเป็นย่านธุรกิจที่สำคัญของโตเกียว

โดยสถาปนิกและนักออกแบบห้องน้ำในโครงการนี้ไม่ได้มองเรื่องความสะอาดและสุขอนามัยแค่เพียงอย่างเดียว ความพิเศษ ของห้องน้ำแต่ละแห่งในโครงการนี้จึงเกิดขึ้นจากประเด็นและโจทย์การออกแบบที่สถาปนิกและนักออกแบบแต่ละคนให้ความสำคัญและสะท้อนออกมาในงานออกแบบของตัวเอง ไม่ว่าจะเป็นเรื่องการสร้างความรู้สึกปลอดภัยและสบายใจในการใช้งาน การออกแบบอาคารเล็กๆให้เป็นจุดหมายตาที่ส่งเสริมภูมิทัศน์เมือง รวมไปถึงประเด็นความเท่าเทียมในการใช้งานที่รองรับความหลากหลายของทุกๆ คนในสังคม เป็นต้น สอดแทรกผ่านการตีความทางรูปทรงอาคาร การใช้เลือกใช้วัสดุ และสีสัน ซึ่งช่วยสร้างภาพลักษณ์และประสบการณ์ของผู้ใช้ห้องน้ำสาธารณะที่แตกต่างจากเดิม

Photo Courtesy of Satoshi Nagare and The Nippon Foundation

ห้องน้ำสาธารณะไม่เพียงเป็นพื้นที่ที่สร้างความรู้สึกสบายใจให้แก่ผู้ที่เข้ามาใช้งานเมื่ออยู่ภายใน แต่ยังสามารถเป็นเครื่องมือสร้างความปลอดภัยให้แก่พื้นที่โดยรอบ เช่น ในงานออกแบบห้องน้ำของสถาปนิก SHIGERU BAN ที่ตั้งอยู่ใน HARU-NO-OGAWA COMMUNITY PARK และ YOYOGI FUKAMACHI MINI PARK ที่มีลักษณะเป็นกล่องโปร่งใสมองเห็นภายในได้ ซึ่งเริ่มต้นมาจากสถาปนิกมองว่าความกังวลใจในการใช้ห้องน้ำสาธารณะนอกจากเรื่องความสะอาดแล้ว คือเราไม่สามารถรับรู้ได้ว่ามีคนอื่นใช้งานอยู่ภายในหรือไม่ ในการออกแบบจึงเลือกใช้กระจกคุณสมบัติพิเศษที่สามารถปรับเป็นโปร่งใสและทึบแสงได้ ให้สัมพันธ์กับการที่มีผู้ใช้งานอยู่ภายใน ไม่เพียงเท่านี้ ในเวลากลางคืน ห้องน้ำนี้จะกลายเป็นกล่องเรืองแสงในสวนสาธารณะที่เปล่งแสงผ่านกระจกใสเฉดสีต่างกัน สร้างความสวยงามและความสว่างให้แก่พื้นที่ ทำให้เกิดความรู้สึกปลอดภัยในสวนยามค่ำคืน อย่างไรก็ดียังคงมีเสียงสะท้อนจากชาวโตเกียวจำนวนหนึ่งที่รู้สึกไม่สะดวกใจที่จะเข้าไปใช้งานห้องน้ำกระจกนี้ เพราะไม่คุ้นเคยกับห้องน้ำสาธารณะที่โปร่งใส ถึงแม้จะมองไม่เห็นจากภายนอกก็ตาม ซึ่งคงต้องใช้เวลาในการสร้างความคุ้นชินสำหรับสิ่งแปลกใหม่ที่สถาปนิกพยายามนำเสนอ

Photo Courtesy of Satoshi Nagare and The Nippon Foundation

แนวคิดเดียวกันนี้มีความคล้ายคลึงกับงานออกแบบของสถาปนิก TAKENOSUKE SAKAKURA ในสวน NISHIHARA ITCHOME ที่ตั้งใจออกแบบห้องน้ำสาธารณะจำนวนสามห้องด้วยแนวคิดจากกล่องโคมไฟกระดาษของญี่ปุ่นที่เรียกว่า Andon เพื่อเพิ่มแสงสว่าง ลดจุดอับทางสายตาในเวลากลางคืน และเป็นจุดหมายตาในสวน โดยเลือกใช้วัสดุอาคารเป็นกระจกทึบแสงสีเขียวที่พิมพ์ภาพของเงาต้นไม้ลงไปบนพื้นผิวและจะมองเห็นลวดลายได้จากภายในห้องน้ำเท่านั้น ซึ่งสถาปนิกคาดหวังว่าความพิเศษเล็กๆ น้อยๆ นี้น่าจะดึงดูดให้คนเมืองพึงพอใจในการใช้งานสิ่งอำนวยความสะดวกและสร้างภาพลักษณ์ที่เชื้อเชิญให้กับสวนได้มากยิ่งขึ้น

Photo Courtesy of Satoshi Nagare and The Nippon Foundation

สถาปนิกรุ่นใหญ่อย่าง TADAO ANDO ก็ร่วมออกแบบห้องน้ำในสวน JINGU-DORI PARK โดยเลือกใช้ผังพื้นวงกลมที่แยกทางเข้าห้องน้ำชาย หญิง และห้องน้ำสำหรับทุกคนอย่างชัดเจน การเลือกใช้ระแนงอลูมิเนียมโดยรอบของ Ando ทำให้เกิดความรู้สึกเป็นส่วนตัวแต่ก็ยังสามารถมองเห็นระหว่างภายนอกและภายในได้ รวมถึงช่วยเอื้อต่อการระบายอากาศและการนำแสงธรรมชาติ เข้ามายังพื้นที่ภายใน ส่วนพื้นที่ทางเดินรอบภายนอกภายใต้หลังคายื่นนั้นเปรียบเสมือนพื้นชานภายนอกบ้านแบบบ้านญี่ปุ่น หรือ Engawa ที่จะช่วยขยายขอบเขตของห้องน้ำหลังนี้ให้ต่อเนื่องไปกับสวนภายนอก และภูมิทัศน์เมืองอย่างกลมกลืน ไม่เพียงเท่านี้ อาคารหลังนี้ยังสร้างประสบการณ์ให้แก่ผู้ที่เข้ามาใช้งานเหมือนได้ยืนพักชมสวนหรือทำหน้าที่เป็นศาลาพักรอช่วงฝนตกตามความหมายของ Ayamadori ที่หยิบยืมมาใช้ในการออกแบบก็ได้

ในสวนชื่อ EBISU EAST PARK ซึ่งหมายถึงปลาหมึกยักษ์นั้น สถาปนิก FUMIHIKO MAKI ออกแบบห้องน้ำสาธารณะ ให้เป็นเสมือนศาลาหลังใหม่ของสวนสาธารณะโดยการแบ่งพื้นที่ห้องชายและหญิงออกเป็นสี่ส่วนอย่างชัดเจนและคลุมพื้นที่ด้วย หลังคาแผ่นบางโค้งสีขาวสร้างรูปทรงแปลกตา ข้อดีจากการเลือกใช้ผังพื้นแบบกระจายศูนย์กลางไม่เพียงช่วยเรื่องการระบายอากาศและเปิดรับ แสงธรรมชาติเพื่อสร้างสุขอนามัยที่ดีต่อการใช้งาน และสร้างความรู้สึกไม่อึดอัดเมื่ออยู่ภายในที่ปิดล้อมเหมือนทั่วไป พื้นที่ตรงกลางระหว่างห้องน้ำทั้งสี่นี้ ยังทำหน้าที่เป็นเหมือนศูนย์กลางใหม่ของสวน เพื่อให้คนทั่วไปสามารถเดินผ่านและกระจายตัวไปยังพื้นที่ต่างๆในสวนอีกด้วย

Photo Courtesy of Satoshi Nagare and The Nippon Foundation

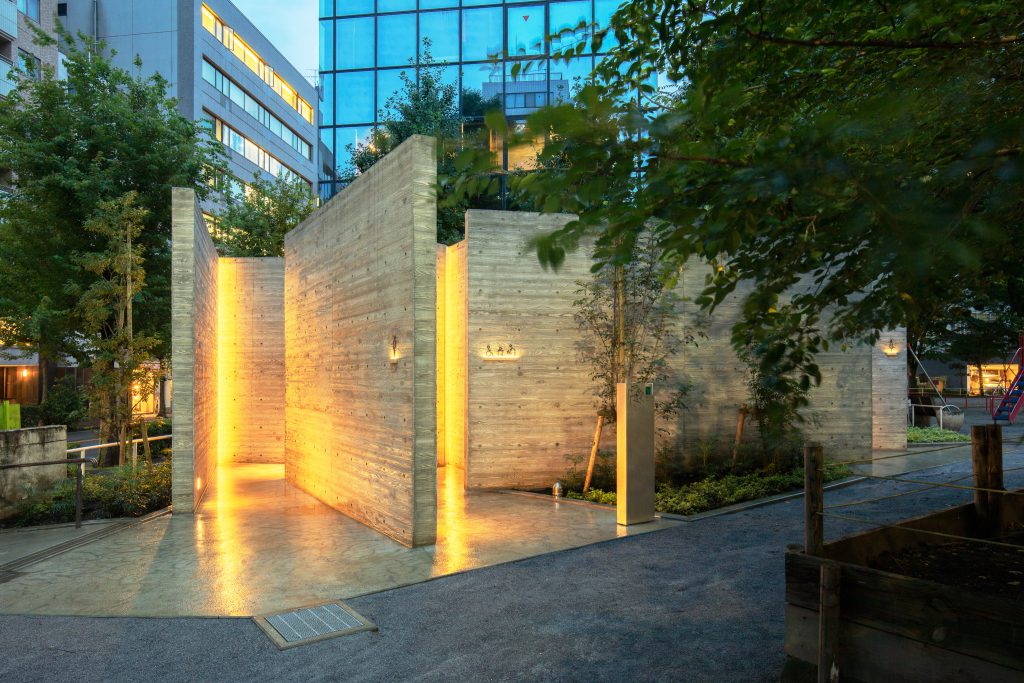

ภูมิทัศน์และบริบทโดยรอบยังคงเป็นประเด็นที่นักออกแบบภายในอย่าง MASAMICHI KATAYAMA จาก WONDERWALL ให้ความสำคัญ และหยิบยกให้เป็นโจทย์ในการออกแบบห้องน้ำในสวน EBISU PARK ผ่านการใช้ผนังคอนกรีตทั้ง 15 ชิ้นที่ทำหน้าที่แบ่งพื้นที่ ห้องน้ำออกเป็น 3 ส่วน สำหรับเพศชาย เพศหญิง และเพศทางเลือก โดยพื้นที่ทั้งสามจะสร้างมุมมองและการเชื่อมต่อกับพื้นที่โดยรอบ ที่แตกต่างกัน นักออกแบบบเลือกใช้ผนังคอนกรีตที่สะท้อนรูปแบบของวัสดุที่ใช้ในการสร้างห้องน้ำของญี่ปุ่นในอดีต Kawaya ที่สร้างด้วยไม้และดินผสานกัน การวางตัวของแผ่นผนังทั้งหมดนี้ยังสร้างความสงสัยคลุมเครือระหว่างภายนอกและภายในของอาคาร ช่วยดึงความสนใจจากผู้คนในสวนให้เข้ามาสร้างปฏิสัมพันธ์และใช้งานอาคาร

Photo Courtesy of Satoshi Nagare and The Nippon Foundation

ในปัจจุบันเมื่อความหลากหลายและซับซ้อนของคนในสังคมนั้นมากกว่าในอดีตเปิดโอกาสของทางเลือกชีวิตที่หลากหลายมากขึ้น ห้องน้ำสาธารณะสำหรับนักออกแบบผลิตภัณฑ์อย่าง NAO TAMURA จึงยกเรื่องความเสมอภาคเท่าเทียมกันของคนทุกวัย และทุกเพศที่ไม่ได้มีเพียงแค่ชายหรือหญิงเท่านั้นมาเป็นประเด็นในการออกแบบ ผู้ออกแบบยังเลือกใช้แผ่นเหล็กสีแดงที่ได้รับแรงบันดาลใจของรูปทรงมาจากการพับกระดาษห่อของขวัญแผ่นเดียวแบบต่อเนื่องของญี่ปุ่นโดยไม่ตัดทิ้งที่เรียกว่า Origata วางในลักษณะเฉียงช่วยแยกทางเข้าของห้องน้ำทั้งสามออกจากกัน โดยแต่ละห้องจะมีพื้นที่ปิดล้อมสามเหลี่ยมเล็กๆ อยู่ด้านหน้าทางเข้า เพื่อทำให้ผู้ใช้งานรู้สึกปลอดภัยและมีความเป็นส่วนตัวก่อนเข้าไปใช้บริการ โดยการเลือกใช้สีแดงสดนั้น ผู้ออกแบบมองว่าแสดงถึง ‘ความเร่งด่วน’ ที่สัมพันธ์กับการใช้งานห้องน้ำสาธารณะที่ไม่จำเป็นต้องใช้เวลานาน

จากประเด็นที่พบร่วมกันในการออกแบบห้องน้ำสาธารณะภายใต้โครงการนี้ เห็นได้ชัดว่าผลลัพธ์และความเป็นได้ ในการออกแบบห้องน้ำสาธารณะสามารถมีความหลากหลายแตกต่างกันไป แม้จะอยู่ในพื้นที่ย่านเดียวกันก็ตาม สะท้อนให้เห็นว่า ห้องน้ำสาธารณะในโตเกียวนี้ ไม่ได้จำกัดความคิดเพียงเรื่องความสะอาดและสุขอนามัยเท่านั้น แต่เกิดจากการตั้งคำถามและสร้างโจทย์ เฉพาะในการออกแบบที่สถาปนิกและนักออกแบบนำเสนอใหม่ถึงความน่าจะเป็นของห้องน้ำสาธารณะในเมือง รวมทั้งยังพยายามสร้างความเชื่อมโยงกับความเป็นญี่ปุ่น ผ่านการตีความคำศัพท์ที่สัมพันธ์กับศิลปะวัฒนธรรมเดิม หรือกระบวนการประดิษฐ์สร้างที่ส่งผลต่อรูปทรงและวัสดุอาคารที่เลือกใช้ จึงทำให้สถาปัตยกรรมพื้นที่เล็กๆ แต่ขาดไปไม่ได้ในชีวิตประจำวันของ ‘โครงการห้องน้ำสาธารณะโตเกียว’ นี้ เป็นเสมือนพื้นที่ทางศิลปะที่นอกจากจะสร้างความสุขตามประโยชน์ใช้สอยแล้ว ยังสร้างความสบายตาภายในเมืองได้อีกด้วย

Photo Courtesy of Satoshi Nagare and The Nippon Foundation

The focus on cleanliness and hygiene, reflected in all the designs are the designers and architects’ interpretations of the issues and challenges surrounding the role and existence of the public facility itself.

The Tokyo Toilet Project: Art Spaces in Tokyo’s Daily Life

Cleanliness and hygiene are fundamental qualities that cities worldwide are showing increasing recognition in, especially in the post-pandemic world where new developments have been initiated to bring people a better quality of life. While Japan has long been praised for the world-leading cleanliness of its cities, many of its people are still unsatisfied with the public toilets in their own country. There are public toilets in Japan that are dark, dingy, dirty, and often rendezvous points of some unpleasant activities, preventing most people from using them out of discomfort. Having witnessed the dilemma, the Nippon Foundation has initiated a collaboration with the Shibuya City government and the Shibuya Tourism Association to launch The Tokyo Toilet Project. The initiative aims to elevate the hygienic standard for the people of Tokyo through 17 fully-equipped and beautifully designed public toilets. The project invited Japan’s renowned designers and architects to create public restrooms for different parts of Shibuya, one of the city’s most prominent business districts. Besides the focus on cleanliness and hygiene, reflected in all the designs are the designers and architects’ interpretations of the issues and challenges surrounding the role and existence of the public facility itself, from safety and functional comfort to their ability to become a pleasant addition to the urban landscape, not to mention the universality of the function that can accommodate diverse demands of all the members in the society. Different interpretations are delivered into various architectural forms, with the use of materials and colors, all attempting to bring a new image to the public restrooms while bringing new experiences to users.

Photo Courtesy of Satoshi Nagare and The Nippon Foundation

In the hands of Shigeru Ban, a public toilet can offer more than just a functional convenience and comfortability, but the ability to serve as a tool that brings a sense of safety to the space where it is situated. Sited in HARU-NO-OGAWA COMMUNITY PARK and YOYOGI FUKAMACHI MINI PARK, the toilets are designed to be transparent when left vacant and turn translucent when occupied with a user inside. The structures illuminate as a light-box at night, radiating lights in different shades of colors amidst the dark public parks. The illumination provides a visually pleasing effect, with desired brightness and creating a sense of safety in the park during the night. Nevertheless, there has been feedback from some of the Tokyo residents who have found themselves uncomfortable using the transparent restrooms since the idea of performing highly private activities behind the translucent walls despite being completely visually inaccessible is something that still requires some getting used to.

Photo Courtesy of Satoshi Nagare and The Nippon Foundation

Takenosuke Sakakura takes on a similar concept with the design he did for the toilet at Nichihara Itchome Park. The three-unit toilet facility takes inspiration from Japanese paper lamps called Andon, with the design that intends to illuminate and brighten up blind corners while being a visible spot in the garden at nighttime. The green translucent glass with a printed pattern of trees that only the person using the toilet can see from inside is a little gimmick that the architect hopes to bring a satisfying user experience through the design’s functional convenience and pleasant-looking appearance.

Photo Courtesy of Satoshi Nagare and The Nippon Foundation

Veteran architect Tadao Ando joins the project with his design for the toilet inside Jingu-Dori Park. Ando designs the circular layout that leads users into the male, female, and accessible cubicles through a clear circulation, providing a sense of privacy while maintaining visual access between interior and exterior spaces. The walkway around the outside periphery is underneath the protruding canopy, inspired by a spanning roof and engawa [Japanese porch] commonly found in traditional Japanese houses. The structural elements seamlessly merge the toilet’s physical boundary to the surrounding landscape of the park and nearby urban area. Not only that, the building offers a spatial experience where users feel like they are taking a rest and enjoy the park’s scenery. In addition to its primary role as a public toilet, the structure functions similarly to a resting pavilion that provides shelter for people when there’s rain, corresponding with the meaning of Ayamadori that Ando had borrowed for the design.

Photo Courtesy of Satoshi Nagare and The Nippon Foundation

For EBISU EAST PARK, known as “Octopus Park” because of its octopus playground equipment, FUMIHIKO MAKI designs the public toilet that also comes with the functionality of the park’s new pavilion. The design divides the male and female quarters into four parts, with the entire functional space roofed with an unusual-looking, thin, undulating sheet. The layout that distributes to the structure’s functional areas accentuates natural ventilation and natural light, improving the toilet’s hygiene as a result. Meanwhile, the open floor plan keeps the enclosed area more spacious than most toilets. It also allows people to walk through and reach other parts of the park.

Wonderwall‘s Masamichi Katayama highlights the surrounding landscape and context in his design. The interior designer incorporates the two elements to the toilet design for the Ebisu Park by using 15 concrete slabs that partition the space into three sections; toilets for males, females,s and all genders. The three functional areas facilitate different perspectives and connections with the surrounding space. Katayama chooses the concrete walls that reflect the characteristics of materials used in traditional Japanese toilets called Kawaya, made of wood and earth. The allocation of the concrete slabs creates interesting ambiguity between interiors and exteriors, attracting the attention of people walking in the park to interact with and use the building.

Photo Courtesy of Satoshi Nagare and The Nippon Foundation

With the diversity and complexity in society being more accepted and enabling more diverse lifestyles, Nao Tamura, product designer, realizes a public toilet design that represents the equality of people of all ages and genders. The various definitions of gender that go beyond the conventional categorization become the subject from which the design is developed. The use of red metal sheets takes inspiration from the Japanese gift-wrapping technique known as Origata. A diagonal line separates the entrances, leading to three different toilets for three groups of users. Each cubicle is fronted with a triangular enclosed space intended to provide a sense of safety and privacy for each user before entering the actual toilet space. The bright red color symbolizes speediness, conveying the relatively shorter time most people use public toilets.

Photo: SS Co., Ltd. Hojo Hiroko.

The common issues found in the designs of public toilets developed under the project indicate mixed results and possibilities of this public facility, despite being sited in the same area or neighborhood. It reflects how ideas behind public toilets in Tokyo are not limited to cleanliness and hygiene but arise from specific questions and conditions the designers and architects have used to develop their design solutions. These ideas propose new possibilities of what urban public toilets can be while trying to facilitate a connection with the Japanese characteristics, whether through different interpretations of terminologies from traditional art and culture or the processes that invent and affect the formation of architectural shapes and materials of choice. Everything, collectively, contributes to these small but indispensable architectural spaces created as a part of ‘The Tokyo Toilet Project.’ With abilities and values equivalent to those of art spaces, these public toilets provide the functionalities they are expected to provide while simultaneously making the urban landscape more visually pleasant.