The initial thoughts that come to mind for most people when a conversation about ‘Smart Home’ is brought up are images of digital screens displaying icons such as a light bulb, lock, thermometer and a bunch of numbers indicating modes and statuses of the equipment installed to bring home dwellers the best possible convenience and comfort, not the actual appearance of a house’s architecture. In general, smart homes are often those homes with automatically operated lighting systems; the type of house that can be air conditioned in advance so the owner arrives back to a perfectly cool home; that can help one efficiently manage energy consumption and can be self-maintained with the systematically installed and functioning digital apparatus.

Text: Panthira Julayanont

Photo courtesy of Taro Hirono, IWAN BAAN, James Morgan Petty, moki and associates and suep.jp except as noted

Download the online journal Issue 05 Home Smart Home Click here

เมื่อพูดถึง “Smart Home” ภาพของหน้าจออุปกรณ์ดิจิทัลที่โชว์รูปหลอดไฟ หยดน้ำ แม่กุญแจ เทอร์โมมิเตอร์ และค่าตัวเลขต่างๆ ของสิ่งอำนวยความสะดวกคงปรากฏขึ้นมาก่อนภาพของตัวบ้านที่เป็นสถาปัตยกรรมรูปแบบใดรูปแบบหนึ่ง โดยทั่วไปแล้ว บ้านที่ชาญฉลาดอาจเป็นบ้านที่มีระบบการทำงานเปิดปิดไฟอัตโนมัติ เปิดแอร์ไว้ให้ตั้งแต่เรายังไม่ถึงบ้าน ช่วยเราบริหารจัดการพลังงานในบ้านอย่างมีประสิทธิภาพ และดูแลตัวเองได้ด้วยอุปกรณ์ดิจิทัลที่ถูกติดตั้งไว้ให้ทำงานร่วมกันอย่างเป็นระบบ แต่หากลองปิดสวิตซ์อุปกรณ์อัตโนมัติเหล่านี้ไป เราจะพบว่าก่อนที่บ้านจะดำเนินมาถึงจุดนี้ ยังมีความชาญฉลาดอีกมากมายซ่อนอยู่ในสถาปัตยกรรมที่เรียกว่า “บ้าน” ซึ่งถูกกลั่นเกลาขึ้นมาจากความตั้งใจจะให้ชีวิตของผู้คนเปลี่ยนแปลงไปในทางที่ดีขึ้น ตอบโจทย์ของสังคมในแต่ละยุคสมัย และในหลายครั้งก็สะท้อนเทคโนโลยีของแต่ละช่วงเวลาไว้อย่างชัดเจน

โจทย์ยุคแรกของบ้าน – ฉลาดที่จะโอนอ่อนไปตามธรรมชาติ

หากศึกษาบ้านจากสถาปัตยกรรมพื้นถิ่นในแต่ละแห่งทั่วโลก จะพบว่าบ้านเหล่านี้คือผลผลิตของการถักทอความรู้ในการอยู่ร่วมกับธรรมชาติอย่างชาญฉลาด โดยสร้างขึ้นมาจากวัสดุที่หาได้ในพื้นที่ นำมาประกอบขึ้นเป็นโครงสร้างที่เรียบง่ายแต่ก็ตอบโจทย์สภาพแวดล้อมในแต่ละพื้นที่เป็นอย่างดี ในหนังสือ “architecture without architects” ของ Bernard Rudofsky หรือ “Shuraku no Oshie 100”集落の教え100, 彰国社 ของ Hiroshi Hara ในปี 1998 ได้เล่าถึงตัวอย่างของบ้านในชุมชนดั้งเดิมจากทั่วโลกที่ไม่ได้มีสถาปนิกคนใดคนหนึ่งเป็นผู้ออกแบบ แต่เป็นผู้คนในชุมชนเหล่านั้นเองที่ร่วมกันกลั่นเกลาบ้านที่เหมาะสมที่สุดขึ้นมาจากรุ่นสู่รุ่น บ้านเหล่านี้แสดงให้เห็นถึงการปลูกบ้านของผู้คนในแต่ละพื้นที่ที่ยังคงพึ่งพิงธรรมชาติและพยายามสร้างสภาวะการอยู่อาศัยให้สบายที่สุดโดยไม่ต้องพึ่งพาอุปกรณ์ไฟฟ้าใดๆ

โจทย์บ้านภายใต้ความเป็นเมือง – มาตรฐานที่ต้องหลากหลาย

การปฏิวัติอุตสาหกรรมและการกลายเป็นเมืองเปลี่ยน “บ้าน” ไปจากยุคก่อนหน้าเป็นอย่างมาก ทั้งในแง่ของกระบวนการผลิต ความหมาย การใช้งาน และรูปแบบทางสถาปัตยกรรม ในยุคที่อุตสาหกรรมเฟื่องฟู ผู้คนจำนวนมากต้องอยู่อาศัยอยู่ในเมืองอย่างแออัด ใช้ชีวิตในบ้านที่ไร้แสงแดดส่องถึง อับชื้น และขาดสุขอนามัย ปัญหาดังกล่าวนำมาสู่การพัฒนาที่อยู่อาศัยโดยภาครัฐบนฐานคิดของการผลิตครั้งละปริมาณมาก (mass production) ซึ่งโยงอยู่กับการผลิตชิ้นส่วนก่อสร้างด้วยระบบอุตสาหกรรม การผลิตบ้านในลักษณะนี้ค่อยๆ ตีกรอบการออกแบบให้ตั้งอยู่บนมาตรฐาน (standardization) บางอย่างเพื่อผู้อยู่อาศัยที่คาดเดาตัวตนได้ไม่ชัดเจนนัก

โจทย์ที่ตามมาจากการสร้างมาตรฐานให้กับบ้านก็คือ จะทำอย่างไรให้บ้านที่ดูจะหน้าตาเหมือนกันไปหมดเหล่านี้มีความยืดหยุ่น เอื้อให้เกิดการสร้างอัตลักษณ์ และทำให้ผู้อยู่อาศัยรู้สึกว่าเป็น “บ้าน” ของตนได้ ความพยายามทลายข้อจำกัดของมาตรฐานนี้ ยังคงเป็นจุดเริ่มต้นของแนวคิดอันชาญฉลาดที่ซ่อนอยู่ในบ้านหลายโปรเจคมาโดยตลอด

ฉลาดที่จะเติบโต

แนวคิดที่ทำให้บ้านสามารถปรับขนาดพื้นที่ใช้สอยได้ เป็นการท้าทายความนิ่งของสถาปัตยกรรมที่ได้รับการออกแบบมาบนมาตรฐานบางอย่างแต่กลับต้องบรรจุชีวิตคนเมืองที่มีพลวัตสูงเอาไว้ สถาปนิกในยุคหนึ่งพยายามหาทางให้สถาปัตยกรรมสามารถเปลี่ยนตัวเองได้อย่างไม่สิ้นสุด โดยชาว Metabolism ในช่วงปี 1960s เป็นสถาปนิกกลุ่มหนึ่งที่มองว่าสถาปัตยกรรมต้องมีชีวิต พร้อมทิ้งเซลล์เก่าที่ไม่ใช้แล้ว เติมเซลล์ใหม่ที่เหมาะสม และเติบโตไปเรื่อยๆ ตามความต้องการของผู้คนและเมือง Sky House โดย Kiyonori Kikutake เป็นตัวอย่างของบ้านที่สะท้อนแนวคิดนี้ออกมาได้อย่างชัดเจน บ้านหลังนี้ลอยอยู่ด้วยเสาแบนสี่เสา มวลอาคารหลักที่ลอยอยู่ด้วยเสาทั้งสี่รวมพื้นที่สำหรับนั่งเล่น นอน และทานอาหารไว้ด้วยกันในผังรูปสี่เหลี่ยมขนาดใหญ่ซึ่งมีระเบียงทางเดินห่อหุ้มไว้โดยรอบ และมีห้องครัวและห้องน้ำเป็นส่วนปะติดที่ย้ายตำแหน่งหรือเพิ่มจำนวนได้ตามความต้องการในอนาคต โดยหลังจากสร้างเสร็จระยะหนึ่งก็มีการแขวนห้องลูกเพิ่มไปใต้มวลอาคารหลัก

หรือ Quinta Monroy โดย Elemental เป็นบ้านโตได้ที่พลิกข้อจำกัดด้านงบประมาณให้กลายมาเป็นจุดเด่นของโครงการ สถาปนิกออกแบบให้มีการสร้างอาคารไว้เพียงครึ่งเดียวและเว้นพื้นที่อีกครึ่งให้ว่างไว้ เพื่อให้ผู้อยู่อาศัยมาต่อเติมเองได้ในภายหลัง โดยการต่อเติมสามารถฝากน้ำหนักไว้กับโครงสร้างหลักที่ให้ไว้ตั้งแต่ต้นได้ วิธีการนี้นอกจากจะช่วยลดต้นทุนการก่อสร้างแล้ว ยังเป็นการเปิดช่องว่างให้ผู้อยู่อาศัยได้สร้างอัตลักษณ์ขึ้นมาผ่านการออกแบบอีกครึ่งตามความต้องการของตน จนเกิดเป็นความหลากหลายที่ไม่อาจสร้างได้ด้วยสถาปนิกเพียงคนเดียว

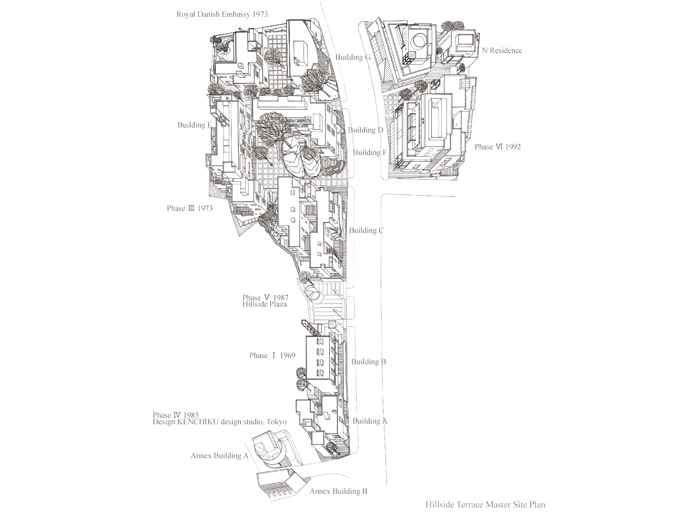

และหากมองในสเกลเมือง อีกโปรเจคหนึ่งที่น่าสนใจในมุมมองของการเติบโตของสถาปัตยกรรมคือ Hillside Terrace Complex I-VI โดย Maki and Associates ในย่าน Daikanyama ซึ่งเป็นโครงการที่มีที่อยู่อาศัยปะปนกับร้านค้า แกลลอรี่ และการใช้งานอื่นที่ส่งเสริมการสร้างพื้นที่สาธารณะที่มีคุณภาพให้กับชุมชน การพัฒนาแบ่งเป็น 7 เฟสที่พาดผ่านช่วงเวลาตั้งแต่ปี 1969 จนถึงปี 1992 การออกแบบแต่ละเฟสดำเนินไปพร้อมกับการสังเกตการณ์ส่วนที่มีการใช้งานแล้ว อาคารที่สร้างทีหลังจึงถูกปรับไปตามความเปลี่ยนแปลงของย่านอย่างค่อยเป็นค่อยไป รวมถึงมีการใส่รายละเอียดที่แตกต่างกันเพื่อสื่อสารความเป็นไปของช่วงเวลานั้นๆ บ้านหลังใหญ่นี้จึงเป็นบ้านที่เติบโตไปพร้อมกับย่านและสร้าง sense of place ให้ย่านไปด้วยพร้อมกัน

ฉลาดที่จะยืดหยุ่น

นอกเหนือจากวิธีการเผื่อสเปซไว้เพื่อรอการเติมเต็มแล้ว อีกแนวคิดหนึ่งที่ทำให้การออกแบบบนมาตรฐานมีความยืดหยุ่นขึ้น คือการออกแบบผังแบบเปิดโล่ง (open floor plan) ผังลักษณะนี้แพร่หลายขึ้นในแถบตะวันตกหลังจากที่ Frank Lloyd Wright เริ่มใช้แนวคิดนี้ออกแบบที่อยู่อาศัยโดยจัดวางพื้นที่นั่งเล่น พื้นที่ทานอาหาร และครัวไว้รวมกัน ในช่วงเวลาใกล้กันนี้ อุปกรณ์ไฟฟ้าหลายอย่างเริ่มเข้ามาเป็นส่วนหนึ่งในชีวิตประจำวันของผู้คนมากขึ้นและลดทอนความจำเป็นของสเปซบางส่วนในบ้านไป ซึ่งน่าสนใจว่าเครื่องดูดควันในครัวก็ถูกพัฒนาขึ้นในช่วงเวลาใกล้เคียงกับช่วงที่ผังแบบเปิดโล่งเริ่มแพร่หลายด้วยเช่นกัน ผังที่ลื่นไหลและเปิดโล่ง พร้อมกับอุปกรณ์ไฟฟ้าที่ช่วยลดขนาดพื้นที่ในบ้านไปเช่นนี้ ดูจะตอบรับกับบ้านในเมืองที่มีเนื้อที่จำกัดได้เป็นอย่างดี และอาจเป็นเหตุผลหนึ่งที่ทำให้ผังแบบนี้ยังคงเป็นที่นิยมเรื่อยมาจนถึงปัจจุบัน

Schroder House โดย Gerrit Rietveld เป็นบ้านอีกหลังที่สร้างทางเลือกให้ผังแบบเปิดโล่งสามารถปรับตัวให้เป็นสัดส่วนยามจำเป็นได้ โดยผังชั้นสองของบ้านถูกออกแบบให้มีผนังบานเลื่อนที่สามารถเลื่อนเปิดให้พื้นที่ทั้งชั้นเชื่อมโยงเป็นหนึ่งเดียวกันหรือเลื่อนปิดเพื่อแบ่งห้องออกเป็นสัดส่วนได้เมื่อต้องการ หรือ Baitasi House โดย dot architects เป็นอีกหลังที่ผนวกแนวคิดที่คล้ายคลึงกันเข้ากับเทคโนโลยีในปัจจุบัน ด้วยการออกแบบให้ผนังปรับเลื่อนได้โดยระบบไฟฟ้าที่ควบคุมผ่าน smart TV ซึ่งรวบรวมเอาอุปกรณ์ smart home อื่นภายในบ้านไว้บนหน้าจอเดียวกัน

ฉลาดที่จะหลอมรวม

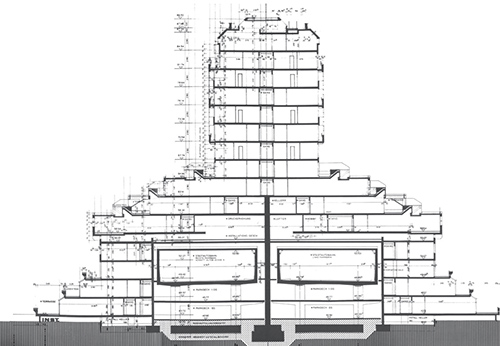

การหลอมรวมที่อยู่อาศัยเข้ากับองค์ประกอบอื่นของเมือง ไม่ว่าจะเป็นโครงสร้างพื้นฐาน หรืออาคารที่ไม่ได้สร้างมาเพื่อการอยู่อาศัยแต่ต้น ก็เป็นอีกแนวคิดที่สร้างอัตลักษณ์ให้ที่อยู่อาศัยไปพร้อมกับใช้พื้นที่เมืองให้คุ้มค่า Autobahnüberbauung Schlangenbader Strasse เป็นตัวอย่างหนึ่งที่รวมที่อยู่อาศัยกับโครงสร้างพื้นฐานเมืองเข้าด้วยกันโดยการวางอาคารคร่อมไว้บนทางด่วน ฐานอาคารที่กว้างขึ้นกลายเป็นพื้นที่ระเบียงส่วนตัวขนาดใหญ่ของบ้านแต่ละหลังลดหลั่นไปเป็นขั้นบันได วิธีการนี้นอกจากจะทำให้ใช้พื้นที่เมืองได้คุ้มค่าแล้ว ยังช่วยเชื่อมต่อเนื้อเมืองทั้งสองฝั่งของทางด่วนเข้าด้วยกันอย่างแยบยลอีกด้วย

The Frøsilo โดย MVRDV ที่ปรับไซโลเก่าเป็นที่อยู่อาศัย โดยปล่อยความกลวงของไซโลไว้เป็นโถงบันไดแล้ววางยูนิตพักอาศัยไว้รอบนอกของโครงสร้างไซโลจนเกิดเป็นผังที่เปิดวิวห้องพักสู่เมือง หรือ Jægersborg Water Tower โดย Dorte Mandrup ที่ปรับหอเก็บน้ำอันเป็นแลนด์มาร์คสำคัญของชุมชนให้เป็นที่อยู่อาศัยของนักเรียนโดยเติมยูนิตเข้าไปด้านบนและใส่พื้นที่พักผ่อนไว้ด้านล่าง ก็เป็นอีกตัวอย่างที่หลอมรวมบ้านไว้กับความทรงจำของเมืองได้อย่างน่าสนใจ

อีกตัวอย่างหนึ่งคือ Torre de David ซึ่งเป็นบ้านที่ไม่ได้มีสถาปนิกเป็นผู้ออกแบบ แต่กลับให้คำใบ้สำคัญหลายประการต่อการออกแบบบ้านในเมือง อาคารนี้เป็นอาคารสำนักงานที่หยุดก่อสร้างกลางคันและถูกทิ้งให้เป็นตึกร้างกลางเมือง Caracas โครงสร้างของอาคารร้างที่มีแต่เสา คาน และพื้น กลายเป็นจุดเริ่มต้นของการสร้างบ้านของผู้คนที่ย้ายจากชนบทเข้ามาแสวงโชคในเมือง ผู้คนขนอิฐเดินขึ้นบันไดกว่าสิบชั้นเพื่อนำไปก่อเป็นผนังเติมเข้าไปในโครงสร้างเดิมจนกลายเป็นพื้นที่อยู่อาศัย ร้านชำ ร้านตัดผม และสถานที่อำนวยความสะดวกต่างๆ ที่จำเป็นต่อคนในชุมชน

โจทย์บ้านในฐานะชิ้นส่วนหนึ่งของโลก – ต้องสื่อสารกับภายนอก

เมื่อเมืองเติบโตมาถึงจุดหนึ่ง ปัญหาทางสังคมและสิ่งแวดล้อมดูจะเป็นโจทย์ข้อต่อไปที่กำลังได้รับความสนใจ การออกแบบบ้านในปัจจุบันเริ่มเปลี่ยนมุมมองจากการหันหน้าเข้าบ้านสู่การหันมองออกไปนอกบ้านมากยิ่งขึ้น ผ่านการตั้งคำถามที่ว่า บ้านจะเชื่อมโยงกับสิ่งที่อยู่ภายนอกอย่างไร จะเป็นจุดเริ่มต้นของการสร้างสังคมรูปแบบใหม่ได้อย่างไร หรือจะทำให้โลกของเราดีขึ้นได้อย่างไรบ้าง

ฉลาดที่จะเป็นผู้สร้างความสัมพันธ์

ในยุคที่เมืองทั่วโลกประสบปัญหาการเข้าถึงที่อยู่อาศัย ผู้คนเผชิญภาวะโดดเดี่ยวและสังคมเปราะบางมากขึ้น บ้านหลายหลังเริ่มปรับบทบาทจากการเป็นเพียงพื้นที่ส่วนตัวสู่การเป็นพื้นที่ทางสังคมรูปแบบใหม่ซึ่งไม่ได้ผูกโยงกับคำว่า “ครอบครัว” ในความหมายเดิมอีกต่อไป บ้านแบบ Co-living เป็นคำตอบหนึ่งที่มาตอบกระแสนี้ โดยการออกแบบบ้านเหล่านี้มีความท้าทายตรงที่การจัดความสัมพันธ์ระหว่างฟังก์ชั่นในพื้นที่ส่วนตัวและพื้นที่ส่วนกลางอย่างสมดุล เพื่อเชื่อมต่อคนแปลกหน้าที่มาอยู่ร่วมกันในระดับที่พอดีและไม่ทำให้รู้สึกอึดอัด ในญี่ปุ่นมีบ้านประเภทนี้ที่น่าสนใจหลายตัวอย่าง เช่น LT Josai Shared House โดย Naruse Inokuma Architects หรือ Tokyo Gasshuku-jo โดย TA+A ที่ออกแบบโดยโอบล้อมพื้นที่ส่วนกลางไว้ด้วยพื้นที่ส่วนตัวและสร้างปฏิสัมพันธ์ระหว่างพื้นที่ทั้งสองในลักษณะสามมิติอย่างน่าสนใจ หรือ Share Yaraicho โดย Spatial Design Studio – Satoko Shinohara ที่ขยายขอบเขตการเชื่อมต่อไปถึงชุมชนรอบบ้าน ด้วยการออกแบบ facade ให้ไม่มีประตูที่ชัดเจน รวมถึงใช้วัสดุที่อนุญาตให้ความเป็นไปภายในบ้านซึมออกสู่ภายนอกได้ลางๆ

Yoshino Cedar House ออกแบบโดย Go Hasegawa ร่วมกับ Airbnb ได้พลิกนิยามของ Co-living space ไปอีกขั้นหนึ่ง บ้านหลังนี้เป็นบ้านหลังแรกที่ Airbnb ลงทุนสร้างขึ้นมาเองใหม่และมีชุมชนเป็นเจ้าของ ไม่ได้ใช้พื้นที่ในบ้านที่มีอยู่เดิม เช่นทั่วไป โดยในวันปกติจะทำหน้าที่เป็นพื้นที่พบปะของผู้คนในชุมชน และกลายเป็นที่พักรับแขกในวันที่มีนักท่องเที่ยวมาเยือน รายได้จากการเข้าพักของนักท่องเที่ยวในบ้านหลังนี้ส่วนหนึ่งจะกลายเป็นเงินกองกลางเพื่องานสาธารณะของชุมชน การขยายขอบเขตความเป็นเจ้าของบ้านหลังหนึ่งไปสู่ระดับชุมชนเช่นนี้ ทำให้บ้านกลายเป็นทรัพย์สินร่วมที่ถักทอความสัมพันธ์ของผู้คนในชุมชนเอาไว้ด้วยกัน

ฉลาดที่จะเป็นอยู่ร่วมกับโลก

สถาปนิกกลุ่มหนึ่งพยายามตอบคำถามที่ว่า บ้านจะทำให้โลกนี้ดีขึ้นได้อย่างไร ด้วยการออกแบบบ้านที่เป็นมิตรต่อสิ่งแวดล้อม ถึงแม้โจทย์นี้จะไม่ใช่แนวคิดใหม่ แต่ก็อาจไม่ได้เป็นเป้าหมายแรกที่คนทั่วไปจะคำนึงถึงในปัจจุบันมากนัก ภายใต้สถานการณ์เช่นนี้ SEUP. ได้ออกแบบ Awajishima House เพื่อตอบแนวคิด Zero Energy House (ZEH) โดยบ้านหลังนี้ตั้งใจลดพลังงานในทุกกระบวนการ ตั้งแต่การลดพลังงานในการขนส่งวัสดุโดยใช้กระเบื้องที่ผลิตจากดินในพื้นที่ การจำลองสถานการณ์ (simulation) ด้วยคอมพิวเตอร์เพื่อหาฟอร์มกระเบื้องสำหรับผิวชั้นนอกของบ้านให้สามารถกันแดดในฤดูร้อนและปล่อยให้แดดส่องเข้าบ้านในฤดูหนาวได้อย่างเต็มที่ การเลือกใช้ผนังดินเป็นฉนวนความร้อน ไปจนถึงการวางระบบพลังงานสะอาดไว้ในบ้าน เช่น ระบบนำความร้อนใต้ดินมาเป็นพลังงานสำหรับเครื่องปรับอากาศ

ในมุมของสิ่งแวดล้อม บ้านพิมพ์สามมิติ (3D-printed house) เป็นอีกนวัตกรรมหนึ่งที่ใช้เทคโนโลยีมาช่วยเพิ่มประสิทธิภาพและลดขยะในการก่อสร้าง ซึ่งในหลายโปรเจค เช่น URBAN Cabin ของ DUS Architects ก็เลือกใช้วัสดุที่ลดภาระทางสิ่งแวดล้อมอย่างพลาสติกชีวภาพ (bioplastic) มาเป็นหมึกพิมพ์ ถึงแม้ว่าบ้านพิมพ์สามมิติจะยังอยู่ในช่วงทดลองและยังไม่แพร่หลายนัก แต่ก็น่าจะเข้ามาเปิดปรากฏการณ์ใหม่ให้การอยู่อาศัยได้อีกหลากหลายรูปแบบหลังจากนี้ เพราะนอกจากจะตอบโจทย์ด้านสิ่งแวดล้อมแล้ว ยังเพิ่มโอกาสที่จะทำให้ผู้คนสามารถสั่งตัด (customize) บ้านให้เป็นไปตามความต้องการได้ง่ายขึ้นอีกด้วย

โจทย์บ้านในอนาคต – ฉลาดร่วมงานกับดิจิทัล

ณ วันนี้ ความฉลาดที่สั่งสมมาในสถาปัตยกรรมที่เรียกว่าบ้าน กำลังถูกท้าทายด้วยอุปกรณ์ดิจิทัลที่เข้ามาบดบังความสำคัญของสเปซบ้านที่จับต้องได้ไปแทบมิด จนคนส่วนใหญ่นึกออกแต่ภาพหลอดไฟหรือแม่กุญแจบนหน้าจอเมื่อถูกถามถึง “Smart Home” นี่อาจเป็นโจทย์สำคัญของสถาปนิกในอนาคตที่จะต้องค้นหาคำตอบต่อไปว่า แล้วบ้านที่ฉลาดในอนาคตควรออกแบบเพื่อให้มนุษย์อยู่ร่วมกับเทคโนโลยีดิจิทัลอย่างสมดุลได้อย่างไร บ้านควรพึ่งพาหรือมอบหน้าที่ให้เทคโนโลยีดูแลคนในบ้านมากน้อยแค่ไหน แล้วสเปซของบ้านที่ทำงานร่วมกับเทคโนโลยีได้อย่างดีจะมีหน้าตาเป็นอย่างไร

สถานการณ์ที่ทำให้คนต้องใช้ชีวิตในบ้านมากขึ้นในตอนนี้ อาจเข้ามาสะกิดบอกเราว่า การพึ่งพาเทคโนโลยีตลอด 24 ชั่วโมงอาจไม่ใช่คำตอบของการใช้ชีวิตอย่างมีคุณภาพสักเท่าไหร่นัก และสถาปนิกยังคงต้องเสาะหาแนวคิดที่จะทำให้บ้านมีสเปซที่เหมาะสมกับวิถีชีวิตในยุคดิจิทัลต่อไปอย่างเข้าอกเข้าใจมนุษย์ รวมถึงไม่ละทิ้งโจทย์ในอดีตที่ยังไม่ได้รับการคลี่คลาย

เมื่อเราลองเปิดสวิตซ์ของเทคโนโลยี Smart Home กลับขึ้นมาอีกครั้งภายใต้โจทย์บ้านในอนาคตข้อนี้ ภาพของสถาปัตยกรรมที่บรรจุเทคโนโลยีเหล่านี้ไว้อาจเริ่มปรากฏให้เห็นขึ้นมาลางๆ พร้อมให้เราจินตนาการต่อเพื่อเติมเต็มหน้าตาของบ้านที่ชาญฉลาดในอนาคตก็ได้

The initial thoughts that come to mind for most people when a conversation about ‘Smart Home’ is brought up are images of digital screens displaying icons such as a light bulb, lock, thermometer and a bunch of numbers indicating modes and statuses of the equipment installed to bring home dwellers the best possible convenience and comfort, not the actual appearance of a house’s architecture. In general, smart homes are often those homes with automatically operated lighting systems; the type of house that can be air conditioned in advance so the owner arrives back to a perfectly cool home; that can help one efficiently manage energy consumption and can be self-maintained with the systematically installed and functioning digital apparatus. But taking away all the automatically operated tools, one would realize that before human homes reached this point of technological advancement, there have always been many smart features hidden in the architecture we call home. They are formed, developed and refined with the intention to change humans’ quality of life for the better, delivering what society expects at different periods in history. On several occasions, residential architecture reflects the technologies that define an era.

A home’s primary tasks- Nature Smart: Compromise and coexist

The study of ‘houses’ as a part of vernacular architecture in areas around the world reveals that this kind of built structure is the product of humans’ evolving wits and skills as they have learned to live with nature over time. These houses are constructed from locally available materials with simple yet effective structures that correspond with local climatic conditions. In the books, “architecture without architects” by Bernard Rudofsky or “Shuraku no Oshie 100”集落の教え100, 彰国社 by Hiroshi Hara in 1998, examples are made of how houses in early human communities from around the world weren’t designed by architects but community members who develop their dwellings through generations. These houses illustrate how humans, despite being in different areas of the world, still rely heavily on nature and create the most comfortable living condition without having to depend on any electrical appliances.

A home in the context of urbanism – Diversified Standards

Industrial revolution and urbanization have changed a ‘house’ into something that is drastically different from what it used to be, from concept, functionality, definition to architectural styles. In the time of the industrial heyday, a large number of people were forced to live in cities of high population density, in homes with little to no exposure to sunlight and extremely poor sanitation. Such problems led to the government’s housing development plans and policies, most of which are based on mass production, which is closely intertwined with industrially produced parts. The construction of this type of house gradually framed residential design to base itself on a certain standardization to serve a more generalized group of users without reflecting that much on the character or identity of an owner. The demands that ensue the standardization of residential design is how to make cookie cutter houses more flexible, and more reflective of the owners’ varying characters and identities, making them feel that these similar-looking houses are their homes. The attempt to demolish the limitations that come with standardization becomes the genesis of the smart concept, which is hidden in several residential projects.

Smart enough to grow

The idea of designing a house to have spaces with adjustable sizes and functionalities challenges the static nature of architecture that has been designed from a certain standardization, which ironically, serves to accommodate the highly dynamic lifestyle of urban habitants. Architects, at one point in time, were finding ways for architecture to be infinitely adaptable. The Metabolism Movement from the 1960s were primarily a group of architects that viewed architecture as a form of living creature, one that has to be ready to shred it’s old, unused cells, before adding newer and more suitable cells in order to continue to grow and cater to the changing demands of people and urban spaces as well as contexts it’s a part of. Sky House by Kiyonori Kikutake is an interesting example of a house that distinctively materializes such a concept. The house is elevated on four flat columns with the main architectural mass hosting a lounging, sleeping and dining area within the large rectangular layout with all sides surrounded by large balconies. The kitchen and restrooms are included as an addition, which can be relocated and expanded to suit future needs. A while after the construction was completed, a baby room was added to the program, underneath the main architectural mass. Quinta Monroy by Elemental or growable house turned the project’s limited budget into one of its most distinctive qualities. The architect intentionally designed only half of a building for each living unit, leaving the other half unoccupied and allowing dwellers to make their own extension later. The existing main structure is designed to bear the weight of the future extension. While the design effectively works around the limited budget with reduced construction cost, it provides dwellers a space, which allows them to add their own identity and character through its extension. What the project ends up creating is the kind of diversity that the architect alone could not entirely contribute.

Hillside Terrace Complex I-VI by Maki and Associates in Daikanyama district of Tokyo is another interesting project, particularly in the aspect of architecture’s ability to grow on an urban scale. The project houses residential and commercial spaces, a gallery, as well as other functionalities that support the existence of high quality public parks. The development was divided into seven phases over the course between 1969 and 1992. The design of each phase continued as the architecture team observed the completed phases to readjust features of the succeeding buildings to suit the evolution of the neighborhood over time with different details added to convey the contemporaneous context of each time period. This big house grows alongside its surrounding environment and brings a sense of place to the neighborhood.

To be Smart is to be flexible

Apart from the provision of spare spaces that wait to be fulfilled, another idea that helps standardization-based design be more flexible is the open floor plan. This particular floor plan has become more widespread in the West after Frank Lloyd Wright reconciled residential design by combining the living and dining area and kitchen together. Around this time period, electrical appliances were becoming a part of people’s everyday life and lessened the necessity of certain spaces of a house. It’s interesting how inventions such as a kitchen hood were being developed around the same time when open plan layout was becoming popular. The open plan and free flowing walls with an electrical appliance that could help reduce the size of a living space was a perfect solution for an urban home with limited functional space, which is one the reasons why such a floor plan is still a favored preference for today’s dwellers.

Schroder House by Gerrit Rietveld is another house that offers alternatives for an open floor plan to be readjusted into proper sections when needed. The second floor of the house is designed to have sliding walls that enable the entire space of the floor to connect or closed to divide the space into rooms. Baitasi House by dot architects is another work that integrates a similar concept to the current technologies with electrical powered adjustable walls that can be controlled via a smart TV, which also includes other smart home features on the same display screen.

To be smart is to assimilate

The assimilation of residential spaces to other components of a city, be it the infrastructures or buildings that were not originally built for human habitation, is another concept of how an identity and character of a dwelling is formed along the maximized use of urban spaces. Autobahnüberbauung Schlangenbader Strasse is another example that integrates a living space to the city’s infrastructure. The residential complex sits above an active freeway with a widened footing that provides a personal balcony for each of the living units, which descend in terraced steps. The design does not only maximize the use of urban space but also thoughtfully links the urban fabrics on both sides of the freeway together.

The Frøsilo by MVRDV transforms a couple of old silos into a residential complex by leaving the voids as the stairways and placing the living units on the outer periphery of the silos. Created is a floor plan that opens all the living units to the view of the city. Jægersborg Water Tower by Dorte Mandrup, has changed the water tower that is the community’s landmark into a student accommodation, adding units on top and the living area underneath, exemplifying how a residential structure assimilates itself to the town’s memory.

Torre de David is fascinating for the fact that it isn’t designed by an architect, yet, sends several interesting signals to how urban residential design can be defined. The building was an office building whose incomplete construction turned it into a deserted structure in the middle of the city of Caracas. The structure of the deserted building with only columns, beams and floors became the starting point of a construction project carried out by the people who moved from their rural hometowns to the city. With the intention to turn the rundown structure into their homes, this group of people carried bricks, and walked up between the ten stories of the building, filling up the wall-less structure and created their own living units with grocery stores, a barber shop and other establishments and facilities that are necessary for the community members’ livelihood.

A house as a part of the world—Communicating with the outside

Once a city has grown to a certain point, social and environmental problems become a subject of interest. Residential design in the current time is seeing a shift in dwellers’ preferences to have the front of the house face outward rather than the other way around. Questions have been asked about how a house can connect to its outside surroundings, and how such an approach can become a beginning of a new type of society or even a better world.

A smart relationship facilitator

In the time when cities around the world are facing a scarcity of homes as people have faced greater difficulty accessing housing. Humans are going through a tougher stage of isolation and society is becoming more fragile. Houses are adjusting their roles as a personal space to a full on social space that no longer associates themselves to ‘family’ in the same sense they used to be. Co-living houses have become one of the answers to this trend. Designing a house of this nature is challenging in the way that it needs to manage the relationship and balance between private and common spaces, bringing together the strangers who share the same living space at the right and comfortable level. In Japan, there are several interesting projects that have adopted this particular residential typology. LT Josai Shared House by Naruse Inokuma Architects or Tokyo Gasshuku-jo by TA+A surround the common areas with private spaces, and facilitate interactions between both types of space into a three dimensional connection.

Share Yaraicho by Spatial Design Studio – Satoko Shinohara extends the boundary of connectivity to the community surrounding the house with the design of the facade that makes the entrance seem obscured and the materials that allow activities inside of the house to be slightly visible from the outside. Yoshiko Cedar House by Go Hasegawa and Airbnb redefines co-living space and takes it to the next level. The house is the first Airbnb-funded accommodation that is owned by a community, unlike other privately owned accommodations on Airbnb’s listing. On regular days, the house functions as a meeting space for community members and an accommodation on the days when there are visiting guests. The income generated from the accommodation fee is added to the fund used for the community’s public affairs. The expansion of the ownership of the house to a community level makes the house a shared asset that intertwines relationships between people in the community together.

To be smart is to coexist with the world

A group of architects are trying to answer the question of how a house can help make the world a better place through environmentally-conscious design. While the question is nothing new, it may not always be the first objective people strive for when building their own homes in this day and age. Under this circumstance, SEUP designs Awajishima House with the Zero Energy House (ZEH) concept with the intention to reduce the use of energy in every possible aspect and process, from transportation (by using the tiles made of local earth), the digitally generated simulation to find the most suitable form for the tiles that would be used as the house’s exterior cladding material. The tiles can protect the house from the summer sunlight but allow natural light to fully make its way into the house’s interior during winter. Earth walls serve as effective heat insulation while the house is equipped with a clean energy system such as the system that uses geothermal energy to power the air conditioners. From an environmental standpoint, 3D-printed houses are another innovation that utilizes technologies to maximize construction efficiency and reduce construction waste. In several projects such as URBAN Cabin by DUS Architects, bioplastic is used as the printing ink for its minimized burden on the environment. While 3D-printed houses are still pretty much in their experimental phase and far from popular, it can open a new door for many other living typologies to come, simply because not only does it ticks several boxes on the environmental checklist, but it will also enable future homeowners to customize their homes according to their desires and preferences.

A home of the future- Smart digital collaborations

At this moment in time, the ‘smartness’ accumulated through the evolution of the architecture we call home is being challenged with digital tools that almost completely overshadow the physical and visible spaces of a home to the point where the majority of people can only imagine the image of a light bulb or a lock on a computer screen when the term ‘smart home’ is mentioned. This is probably a great challenge for architects in the future to continue their quest for the right answer to the question of how a smart home in the future should be designed to maintain a sense of balance with the coexistence of humans and technologies. To what extent should a home rely on or assign technologies the role to take care of its inhabitants, and what should a living space that will work in tandem with all these new technologies look like?

The ongoing situation that is now forcing people to spend more time at home is probably a reminder that relying on technology at all times may not the answer to quality living. Architects also still have to search for other possible concepts to create the most suitable living space that will suit life in the digital age with a true understanding of humans without discarding the past unanswered questions. Turning on the switch of the smart home technology under the challenging tasks that a home of the future is expected to fulfill, an image of architecture, equipped with smart technologies, is becoming more apparent and ready for us to envision what a smart home will actually look like in the future.

—-

ภัณฑิรา จูละยานนท์ อาจารย์ประจำภาควิชาการวางแผนภาคและเมือง คณะสถาปัตยกรรมศาสตร์ จุฬาลงกรณ์มหาวิทยาลัย สนใจเกี่ยวกับความสัมพันธ์ระหว่างสถาปัตยกรรมกับวิถีชีวิตในเมือง ปัจจุบันทำงานวิจัยเกี่ยวกับอนาคตการอยู่อาศัย

Panthira Julayanont is a lecturer at Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Faculty of Architecture, Chulalongkorn University. Her interests lay in relationships between architecture and urban life. She is currently conducting a research project on the futures of living.