What happens after we die? From where or what is one conceived? And the most important question, how are we born? How do we live and die? Attempting to question a development process or thought process in a linear manner without considering the connected causes and effects is nothing new in society. Even within the architectural profession, to question the architectural community and industry whose focus is mainly if not merely on the physicality of built structures has been contemplated a countless number of times.

Text: Pornpas Siricururatana, Ph.D.

Download the online journal Issue 04 Towards Circular Living Click here

Photo: Roland Halbe

Circular of Life เกิด แก่ เจ็บ แล้วก็ ตาย

ตายแล้วไปไหน เกิดจากอะไร และที่สำคัญที่สุด เกิด อยู่ และตายอย่างไร ความพยายามที่จะตั้งคำถามกับกระบวนการพัฒนาแบบ linear หรือกระบวนการคิดที่ไม่คำนึงถึงผลที่เชื่อมโยงไม่ใช่เรื่องใหม่อะไรในสังคม ในวิชาชีพสถาปัตยกรรมเอง การตั้งคำถามกับวงการวิชาชีพที่เทจุดสนใจไปที่ลักษณะของตัวสถาปัตยกรรมที่จะสร้าง ถูกตั้งคำถามมาแล้วนับครั้งไม่ถ้วน ความสนใจในกระบวนการสร้างและการได้มาซึ่งทรัพยากร รวมถึงความพยายามในการคิดให้ครบวงจรนั้น มีให้เห็นมากในอุดมการณ์ของความเคลื่อนไหวหลายๆอย่าง ในยุค 60s โดยเฉพาะอย่างยิ่ง บั๊กกี้ หรือ Buckminster Fuller กับปรัชญาแนวคิดที่เห็นได้ชัดในหนังสือ Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth ของเขา ที่มองโลกเป็นเหมือนยานลำหนึ่งในอวกาศที่มีเชื้อเพลิงและทรัพยากรที่จำกัด น่าจะไม่ใช่เรื่องบังเอิญที่สถาปัตยกรรมพื้นถิ่น ก็เริ่มได้รับความสนใจในยุคนี้เช่นเดียวกัน สถาปัตยกรรมพื้นถิ่น เป็นตัวแทนที่ดียิ่งในการตั้งคำถามกับกระบวนการคิดแบบ Linear ที่มองข้ามวงจรชีวิตและความสัมพันธ์ที่เชื่อมโยง ทั้งในแง่วัสดุและกระบวนการสร้าง รวมถึงปัจจัยด้านสังคมเศรษฐกิจ และการบริหารจัด การบำรุงรักษาสิ่งแวดล้อมนั้นๆ ในปัจจุบันสถานการณ์ของทรัพยากรและระบบนิเวศของโลกรุนแรงกว่ายุคของบัคกี้มาก กระบวนการคิดแบบครบวงจรไม่ใช่ alternative อีกต่อไป แต่กลายเป็น Norm ของสังคมในวงการสถาปัตยกรรม ประเด็นที่เคยถูกละเลย ไม่ว่าจะเป็นการได้มาซึ่งทรัพยากรและวัสดุในการก่อสร้าง การทำงานและพฤติกรรมของอาคารหลังจากสร้างเสร็จ รวมไปถึงวิถีของอาคารเมื่อหมดอายุ ทั้งกระบวนการริ้อถอนและย่อยสลาย กลายเป็นส่วนหนึ่งที่ขาดไม่ได้ในกระบวนการคิดของสถาปนิก

จาก ขุด / ถลุง สู่ ปลูก / เลี้ยง

ประเด็นแรกๆ ที่สถาปนิกทำงานด้วย คือการตั้งคำถามกับวัสดุก่อสร้างในระบบอุตสาหกรรม อย่างคอนกรีต และเหล็ก หรือ วสดุสังเคราะห์ต่างๆ ที่เกิดจากทรัพยากรที่จำกัด และในหลายกรณี ต้องใช้พลังงานมหาศาลในการได้มาซึ่งวัสดุ ความคงทนถาวรที่เคยเป็นที่ต้องการ ถูกเชื่อมโยงกับความแข็งทื่อและไม่ยืดหยุ่น ความเปราะบางของวัสดุ organic ที่เคยถูกตราหน้าว่าไม่ทน หรือเน่าโทรม กลายมาเป็นส่วนหนึ่งของแบรนดิ้งโครงการที่ป่าวประกาศว่า นี่คือวัสดุที่ย่อยสลายได้ สถาปนิกหลายกลุ่ม หันไปทำงานกับวัสดุ organic ที่นอกจากจะสามารถ“ย่อยสลาย” ได้แล้ว ยังสามารถ“ปลูก” ขึ้นมาทดแทนได้ สู่วัสดุที่มีการหมุนเวียนอย่างไม้ไผ่ หรือดิน มีให้เห็นมากขึ้นมากในช่วงสิบกว่าปีที่ผ่านมา ในประเทศไทยเองก็เช่นกัน งานของ ธ.ไก่ชน โดยคุณ ธนพัฒน์ บุญสนาน หรืองานสถาปัตยกรรมดินของ La Terre น่าจะเป็นตัวอย่างที่ดีของการทำงานกับวัสดุเหล่านี้ในบริบทของเมืองไทย นอกจากนี้ สถาปัตยกรรมไม้ก็กลับมาผงาดเป็นพระเอกอีกครั้งในหลายๆพื้นที่ในโลก ในฐานะวัสดุ “organic” ที่มีความยืดหยุ่น (ในวงจรชีวิต) และสามารถเก็บกักเก็บคาร์บอนได้ ความพยายามที่จะใช้วัสดุหมุนเวียน ไม่ได้หยุดอยู่แค่การกลับไปใช้ วัสดุที่ “ปลูก” ได้เท่านั้น แต่ยังมีงานอีกกลุ่มที่มองไปถึงกระบวนการก่อสร้าง และบางครั้งก็มองไปถึงชีวนิเวศระหว่างกระบวนการด้วย หลายคนอาจจะยังจำผลงาน The truffle ของ Ensamble Studio ของ Anton Garcia-Abril กับ Debora Mesa ได้ ที่ทำงานกับกระบวนการก่อร่างสร้างตัวของสถาปัตยกรรม ที่เอาสิ่งมีชีวิตมาเป็นส่วนหนึ่งของกระบวนการ

ก้อนฟางที่ถูกวางลงในหลุมดินที่ขุดแล้ว คือตัวแทนของ “ที่ว่างในอนาคต” โดยหลุมดินและฟางทำหน้าที่เป็น formwork ซึ่งเมื่อเสร็จกระบวนการเทและผ่าก้อนคอนกรีตแล้ว พวกเขาก็อัญเชิญ วัวตัวน้อย ชื่อ paulina มาช่วยรับประทานฟาง จน “ที่ว่างในอนาคต” ค่อยๆ ปรากฏตัวออกมาเป็นสถาปัตยกรรมที่ poetic ไม่แพ้กระบวนการของมัน The truffle เป็นตัวอย่างที่เหมือนจะช่วยกระซิบบอกเราว่า กระบวนการสร้างไม่จำเป็นต้องน่าเบื่อหรือมีสูตรสำเร็จ แต่อาจจะนำมาซึ่งสถาปัตยกรรมที่เสน่ห์และสนุกได้ก็เป็นได้ หรือสถาปัตยกรรมล้ำๆไปอีกขั้วอย่าง “Probiotic” พาวิลเลี่ยน โดย The Living ในงานเวนิสเบียนนาเล่ ปีนี้ ที่ตั้งคำถาม กับการสร้างสิ่งแวดล้อมที่คำนึงถึงแต่มนุษย์อย่างเดียว แต่ไม่เป็นมิตรกับ microbiome จิ๋วๆ ที่ท้ายที่สุดแล้ว อาจเกิดผลเสียกับมนุษย์เอง โดย The Living ทำงานกับวัสดุที่จะช่วยเปิดพื้นที่ให้ชีวนิเวศจุลชีพ หรือ microbiome จิ๋วๆ สามารถอยู่ไปพร้อมๆกับมนุษย์ได้ หรือ Neri Oxman กับทีมที่พยายามสร้างสิ่งแวดล้อมด้วยสิ่งมีชีวิต ที่เห็นได้ในงานอย่าง Silk Pavilion และ Ocean Pavilion ของเขา งานล้ำสุดๆเหล่านี้ แม้ว่าจะยังอยู่ในระยะทดลองอยู่มาก แต่ก็น่าจะเป็นอีกตัวอย่างที่ดีจะช่วยเปิดพื้นที่และตั้งคำถามกับการก่อสร้างในปัจจุบัน ในขณะเดียวกันก็น่าจะช่วยให้คำว่า “คิดให้ครบวงจรนั้น” มันหมายถึงอะไรกันแน่

Material Flow / Material Bank

คงปฏิเสธไม่ได้ ว่าการใช้วัสดุ “organic” อย่างเดียวในการออกแบบสถาปัตยกรรมยังมีระยะห่างจากความเป็นจริงของ ecosystem ของวงการก่อสร้างในปัจจุบันอยู่มาก และก็คงไม่ใช่เรื่องบังเอิญ ที่หนึ่งในผู้เขียน Cradle to Cradle เป็นสถาปนิก แนวความคิดแบบ Cradle to Cradle (not cradle to grave!) หรือความพยายามที่จะเปลี่ยนขยะให้เป็นเงิน มีให้เห็นในหลายๆพื้นที่ของวงการสถาปนิก ไม่ว่าจะเป็นในประเทศไทยเอง อย่างชุดงานอัพไซเคิลของ รศ.ดร.สิงห์ อินทรชูโต หรือในต่างประเทศ อย่างงานของ Rotor ที่เบลเยี่ยม ที่ทำงานกับ material flow ในวงการก่อสร้าง โดยการพยายามสร้างโครงข่ายของวัสดุ เพื่อให้เกิดการหมุนเวียนมากขึ้น โดยไม่ต้องกลายเป็นขยะก่อน ความพยายามในลักษณะเดียวกับ Rotor มีให้เห็นได้ในโครงการวิจัย Building As Material Bank หรือ BAMB โดยสหภาพยุโรป ที่ตั้งคำถามกับปริมาณวัสดุเหลือทิ้ง และปริมาณทรัพยากรที่ถูกใช้ในอุตสาหกรรมก่อสร้างในปัจจุบัน

แนวคิดของ BAMB คือการเปลี่ยนมุมมองจากการมองอาคารในฐานะ product ที่ถูกสร้าง เพื่อใช้และเมื่อหมดอายุก็จะถูกรื้อทิ้ง แต่มองว่าอาคารเป็นสภาวะหรือ state ของวัสดุ ที่พร้อมจะเปลี่ยนไปสู่สภาวะใหม่ในมุมมองลักษณะนั้น อาคารเป็นเหมือนธนาคารของวัสดุ เป็นการเก็บวัสดุไว้ ณ สถานะของอาคาร ที่เมื่อถึงเวลา ธนาคารนี้ก็พร้อมจะปล่อยวัสดุเหล่านี้กลับออกมาสู่วงจรอีกครั้ง แน่นอนว่าการที่จะทำให้เกิดสภาวะนั้นได้ไม่ใช่เรื่องง่าย เราคงคุ้นตากันดีกับพื้นที่ตั้งงานของอาคารที่ถูกทุบและรื้อ ที่แม้ว่าวัสดุหลายๆส่วนจะถูกเก็บมาหมุนเวียนให้กลับมาใช้ได้อีกครั้ง แต่ก็ยากที่จะห้ามไม่ให้เกิดขยะปริมาณมหาศาล ความพยายามของ BAMB คือความพยายามที่จะออกแบบอาคารที่ไม่ได้เป็น product แต่เป็นการออกแบบสภาวะ หรืออาจะเรียกได้ว่าเป็นการออกแบบวิธีการหยุดเวลาของวัสดุที่สามารถเปลี่ยนสภาพ และแยกย้ายออกจากกันได้ แนวความคิดลักษณะนี้ บางคนอาจจะรู้จักในชื่อว่า Design for Disassembly ที่มองไปที่ความแตกต่างของ Disassembly และ Demolition ว่าต่างกันที่ความสามารถในการคืนสภาพ หรือที่ BAMB เรียกมันว่า Reversible Design นั้นเอง มันคือการออกแบบอาคารที่มองไปถึงฉากจบว่ามันจะจบอย่างไร (หรือมันจะไปมีชีวิตใหม่อย่างไร) โดยให้ความสำคัญกับความอิสระขององค์ประกอบ (Independency) และความสามารถในการแลกเปลี่ยน (exchangeability) หรืออาคาร Good Cycle Building Head Office ของบริษัทรับเหมาเก่าแก่ ในนาโกย่า ประเทศญี่ปุ่น ที่เพิ่งรีโนเวทเสร็จใหม่ๆ ก็เป็นหนึ่งในตัวอย่างของการให้ความสำคัญวงจรชีวิตของวัสดุ ในกระบวนการรีโนเวท โดยใช้ประโยชน์จากวัสดุเหลือใช้ที่เกิดขึ้นในกระบวนการก่อสร้างให้มากที่สุด เช่น การใช้ดินที่เหลือจากการก่อสร้าง โดยแทนที่จะเอาไปทิ้ง (ซึ่งก็ต้องใช้เงินในการทิ้งด้วย) แต่เอามาพอกทำผนังคล้ายบ้านญี่ปุ่นในสมัยก่อน ซึ่งผนังดินช่วยปรับระดับความชื้นในพื้นที่ทำงาน หรือความพยายามในการให้ผู้ใช้อาคารซึ่งก็คือพนักงานในบริษัท เข้ามามีส่วนร่วมในการก่อสร้าง

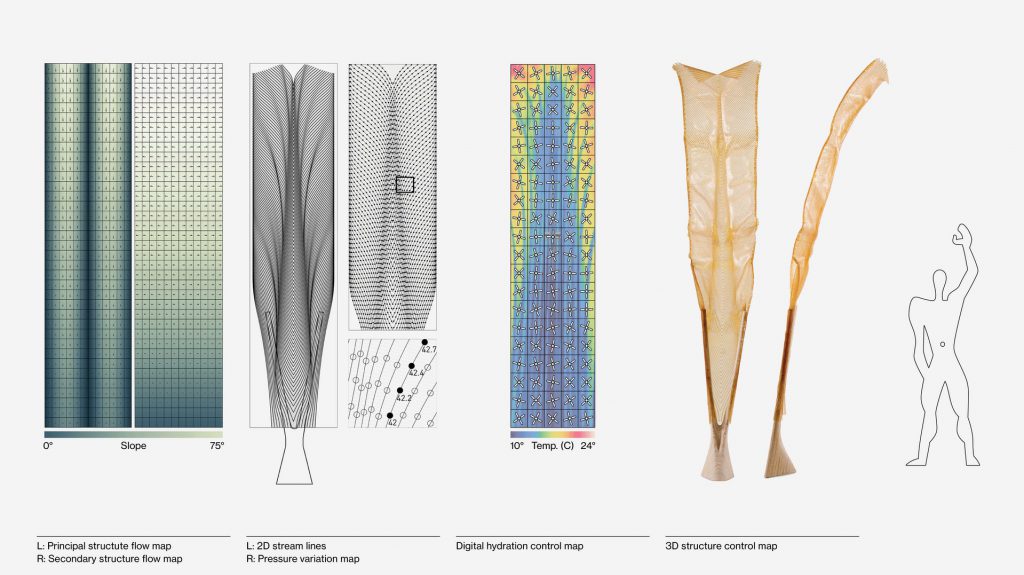

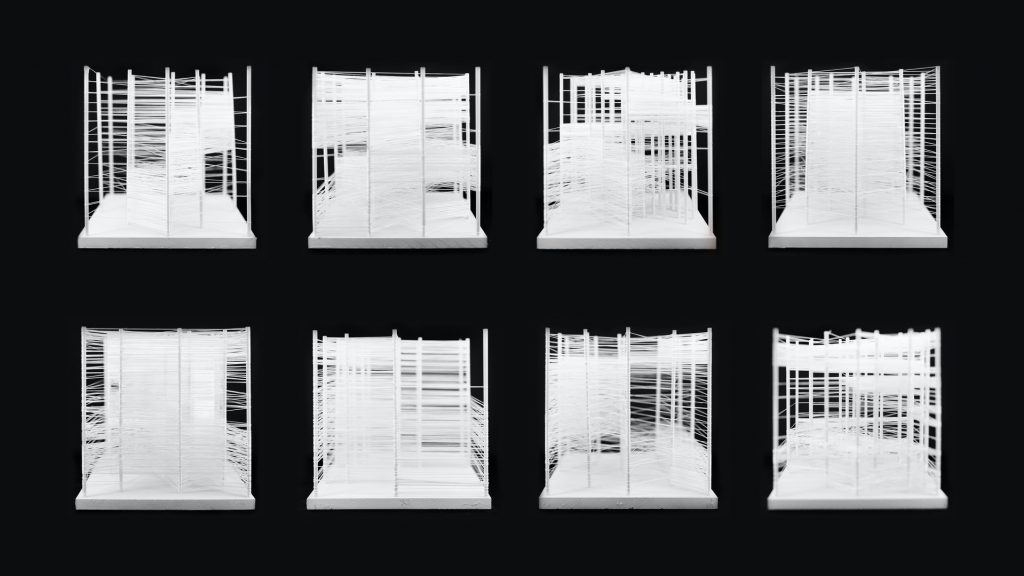

Structural Skin Prototype

Photo: Neri OxmanStructural Venatuin Pattern Variations

Photo: Neri Oxman

จากทุบรื้อทิ้ง สู่การออกแบบวิธีการตาย

ความพยายามในอาคารในฐานะสภาวะ ไม่ได้หยุดอยู่ที่สภาวะการรวมตัวของวัสดุเท่านั้น ตัวอย่างการเปลี่ยนแปลงของอาคาร Sony Building หรือที่หลายคน รู้จักในชื่อของ Sony Ginza Park น่าจะเป็นตัวอย่างที่ดีอีกอันของมองอาคารในวงจรที่ยาวกว่า เมื่อวันที่ 29 กันยายน ที่ผ่านมา Sony Ginza Park ปิดฉากการให้บริการสามปีลง ด้วยงานที่ชื่อว่า Last Day in the Park ที่รวมถึงงานเสวนาแบบเปิดอกระหว่างเจ้าของโครงการ ทีมงานที่เกี่ยวข้อง และนักวิจารณ์ แม้ว่าจุดหมายปลายทางสุดท้ายของโซนี่ คือการสร้างอาคารใหม่ที่มีกำหนดเสร็จสิ้นในปี 2024 แต่กระบวนการก่อนจะเข้าสู่การสร้างอาคารใหม่ได้รับการออกแบบและให้เวลาอย่างเต็มที่ ย้อนไปตั้งแต่ช่วงปี 2013 โดยทีมงานกลุ่มใหญ่ที่รวมถึงนักประวัติศาสตร์สถาปัตยกรรม ภัณฑารักษ์ และนักออกแบบหลายแขนง

สิ่งที่พวกเค้าทำคือการยืดขยายระบวนการรื้อ ให้ผู้คนได้มีโอกาสสัมผัสอาคารในอีกสภาวะหนึ่ง ไม่ว่าจะเป็นช่วงปี 2016 ที่เปิดอาคารก่อนรื้อจริงจัง ออกเป็น concept store ในชื่อ Park-ing Ginza หรือ ระยะเวลาสามปีของ Ginza Sony Park ที่นอกจากเป็นการเปิดโอกาสให้ผู้คนได้ทักทาย และกล่าวอำลาอาคารเก่าแล้ว ยังทำหน้าที่เป็นพื้นที่เก็บข้อมูลพฤติกรรมของผู้ใช้งานในสถานที่จริงและสภาวะเสมือนจริง และเป็นเครื่องมือโปรโมทและรีแบรนด์บริษัทให้กับ Sony ไปในตัวแน่นอนว่า คำถามที่ว่าแล้วจะทุบไปทำไม หรือการทิ้งตัวเลือกของการรีโนเวทอาคารไปนั้น ดีจริงหรือ อาจจะยังเหลืออยู่ในใจของหลายๆคน แต่อย่างน้อยที่สุด น่าจะกล่าวได้ว่าอาคาร Sony Building ได้ตายอย่างสมเกียรติ กระบวนการรื้อถอนถูกออกแบบและให้ความสำคัญด้วยกลุ่มคนที่เห็นคุณค่าของอาคาร ทั้งในแง่คุณลักษณะอาคารเชิงกายภาพและพฤติกรรมของอาคาร ชิ้นส่วนของ façade ถูกทรีตอย่างทะนุถนอม แล้วทำออกมาเป็น product เป็นของที่ระลึก ประหนึ่งตัวแทนของผู้ตาย ความเป็นสาธารณะที่เรียกได้ว่าเป็นหัวใจของอาคาร Sony Building เก่า ถูกสานต่อผ่านคำว่า Park ที่ค่อยๆถูกตีความผ่านสภาวะต่างๆ ของอาคาร

จริงๆ แล้ว เราอาจจะมองกระบวนการทั้งหมดนี้เป็นทั้งกระบวนการ Rebrand และโฆษณาอาคารใหม่ ที่ใช้ประโยชน์จากกระบวนการในทุกๆ ระดับ ที่นอกจากจะเป็นการตั้งคำถามกับการรื้อแล้วสร้างใหม่ ยังเป็นการตั้งคำถามกับระยะเวลาและวิธีการออกแบบอาคาร ที่ปกติต้องกระทำในระยะเวลาที่จำกัดมาก (เมื่อเทียบกับอายุของอาคาร) และไม่สามารถทดลองจริงได้ เรียกได้ว่าเป็นการออกแบบวิธีการตาย ให้ชีวิตของอาคารหลังหนึ่งสามารถมีโอกาสช่วยกำหนดลักษณะและพฤติกรรมของอาคารที่จะเกิดขึ้นใหม่ได้เลยทีเดียวตัดภาพมาที่ประเทศไทยเมื่อต้นพฤศจิกายนที่ผ่านมากับการทุบสกาล่าทิ้งลง ยิ่งชวนให้คิดว่านั่นคือวิธีการตายที่ดีที่สุดของสกาล่าแล้วจริงๆหรือ ทางออกที่ยั่งยืนคงไม่มีทางเป็นไปได้ ถ้าขาดการร่วมมือจากหลายๆฝ่าย โดยเฉพาะอย่างยิ่งเจ้าของโครงการที่เปิดกว้างและมีวิสัยทัศน์

Outro

หลายๆคนที่โตในประเทศไทยในยุค 90s อาจจะยังจำได้ว่า ตอนเด็กๆถูกสอนว่าการใช้ผลิตภัณฑ์ไม้เป็นต้นเหตุของการตัดไม้ทำลายป่า ยังจำได้ว่าตอนที่ไปอยู่ญี่ปุ่นใหม่ๆแล้วที่โรงเรียนสอนว่าการใช้ไม้เป็นการรักษาป่า ก็รู้สึกงงเป็นอย่างยิ่งว่าทำไมวิธีคิดมันถึงต่างกันคนละขั้วได้ขนาดนี้ แน่นอนว่าส่วนหนึ่งเพราะเป็นการพูดถึง “ไม้” คนละชนิดที่โตด้วยความเร็วที่แตกต่างกันมาก แต่เหนือกว่านั้น น่าจะเป็นมุมมองของวงจรที่แตกต่าง และความแตกต่างของประเด็นที่นำมาคิด ไม่ว่าจะเป็นประเด็นด้านสังคมเศรษฐกิจ หรือการตอบโจทย์ system ที่แตกต่างกัน คอนกรีตเองที่มักจะถูกตราหน้าว่าเป็นตราบาปของยุคโมเดิร์น แต่ปัจจุบันก็มีวิจัยหลายๆ ชิ้นที่ออกมาโต้แย้งว่าจริงๆแล้ว concrete อาจจะเป็นวัสดุดักคาร์บอนชั้นยอดก็เป็นได้ ความก้าวหน้าของการทำงานกับ return concrete รวมถึงการรีไซเคิลคอนกรีต อาจจะช่วยเปลี่ยนค่านิยมต่อวัสดุที่สุดจะพลาสติกนี้อีกครั้งในอนาคตอันใกล้ หรือในทางกลับกัน การวิจัยไม้หรือวัสดุ organic ต่างๆ ในปัจจุบัน อาจจะช่วยเปิดพื้นที่สร้าง ecosystem แบบใหม่ให้วงการก่อสร้างก็เป็นได้ ประเด็นคือ “Circular” ของคุณครอบคลุมอะไรบ้าง และมันคือ Circular ของอะไร อย่างที่นักวิจารณ์หลายคนเปิดประเด็นไว้ วิธีคิดแบบ Circular จริงๆแล้วมีความอันตรายแฝงอยู่ เพราะเป็นความคิดที่ตั้งอยู่บนสมมติฐานว่าเราสามารถคิดให้ครบวงจรได้ แต่จริงหรือที่เราสามารถคิดให้ “ครบ”ได้ ในเมื่อวงจรนี้อาจจะเป็นวงจรเปิด ไม่ใช่ Closed system ก็เป็นได้? คงไม่มีคำตอบสำเร็จรูปสำหรับเส้นทางสู่ Circular Living สิ่งที่สำคัญน่าจะเป็นการคิดและตั้งคำถามกับสิ่งที่ทำอยู่ และพื้นที่ที่คุณทำงานอยู่มากกว่า ต่อให้คุณปลูกต้นไม้หรือใช้วัสดุ “ออร์แกนิค” มากแค่ไหน มันอาจจะกลายเป็นแค่ Green washed หรือ Social washed ก็เป็นได้ หากไม่มีการคิด ตริตรองอย่างพิถีพิถัน และไม่มีความร่วมมือหรือความเข้าใจในกลุ่มผู้เกี่ยวข้อง อย่างที่เค้าว่ากัน การกระทำต่อเนื่องเท่านั้นที่จะเป็นคำตอบ เพราะหนทางสู่ Circular Living ณ วันนี้ ที่ประเทศนี้ น่าจะต้องเดินทางกันอีกยาวไกล

Circular of Life- Being born, growing old, getting sick, making the final departure

The interest in the creation process and acquisition of resources, as well as attempts to achieve a truly comprehensive thought process was somewhat flourishing within several ideologies and movements emerging in the 1960s. It was particularly discussed as a part of the philosophical concept proposed by Buckminster Fuller in his book, Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth, which looks at the world as a spaceship with limited fuel and resources. It’s barely a coincidence that vernacular architecture was starting to gain more recognition around this time period. Vernacular architecture is a good and solid representation of the way one would question the linear thought process, which overlooks the cycle of life and interconnected relationships. Whether it is from the dimension of materials, construction processes, socio-economic factors and the management of resources and the environment.

At the moment, the current situation surrounding the world’s resource and ecological crisis is far worse than the time when Fuller wrote about in his book. A comprehensive thought process isn’t just an alternative but now a norm in society. Within the architectural industry, issues that were once neglected, be it the procurement of resources and construction materials, functions and behaviors of completely constructed architecture, all the way to the method used to handle a built structure once it reaches the expiration date, whether it’s the demolishing or decomposing process of architecture, everything has unquestionably become indispensable and integral parts of architects’ thought processes.

Photo: Good Cycle

From excavating and exploiting to growing and nurturing

One of the issues that architects work with is questioning construction materials within the industrial system, Materials such as concrete and steel, or synthetic materials invented due to limited resources, in many cases, looking into how a massive amount of energy is needed for a certain material to be produced and obtained. The once demanded quality of durability is not associated with rigidity and inflexibility, while the fragility of organic materials, which were once shunned for their ephemerality and deterioration, has become a part of a project’s branding, unabashedly shouting that it, too, uses decomposable materials. More groups of architects are now working with organic materials that are not only decomposable but can be re-grown sustainably. The eyes of architects are now looking toward circular materials such as bamboo or earth, and projects using this type of materials are growing in number. In the past decade, Thailand has seen works by architects such as Tanaphat Boonsanan of Thor Kaichon or the earth architecture by La Terre, all setting good and inspiring examples of how architecture can make use of these circular materials within the context of Thailand. In addition, wooden architecture is taking center stage in several parts of the world with wood now attaining the status of an organic material with its flexible life cycle and ability to capture carbon.

The attempts to use circular materials do not stop at a return to use growable materials. There’s a genre of works that look beyond materials to the construction process and, at times, the biome of the process. Many may still remember The Truffle, a project by Anton Garcia-Abril’s and Debora Mesa’s Ensamble Studio and how it experiments on the construction process of the architecture itself by incorporating a living organism as a part of the process. Hay bales are laid in the excavated pit, which represents the ‘Space of the Future’. The pit and hay bales function as a formwork. Once the concrete was poured in and the concrete mass was cut, the architects brought in a calf named Paulina to eat the hay, and gradually the ‘Future Space’ had appeared, revealing itself as a work of architecture whose existence is just as poetic as the process of its conception.

The Truffle is an interesting example in the way it subtly whispers that a construction process doesn’t need to be boring or predictable but it has the potential to be something that can deliver a fun and charming work of architecture. Towards the other end of the spectrum, the futuristic nature of the “Probiotic” Pavilion by The Living at this year’s Venice Biennale questions the human-centric environment created without a good enough consideration for micro biomes, and how the environment will eventually end up bringing negative effects on humans themselves. The Living works use materials that help to create a space where microbes and humans can coexist. There is also a case where Neri Oxman and his team, who together attempt to create an environment out of living creatures with projects such as Silk Pavilion and Ocean Pavilion. While all these highly progressive projects are still in a very experimental phase, they set incredible examples that will continue to pave the way and make more room for us to question the construction processes that are being carried out today. At the same time, they encourage the design and architectural industry as well as the public to contemplate what the term ‘comprehensive thinking’ really means.

Photo Courtesy of La Terre Photo Courtesy of La Terre

Material Flow / Material Bank

It’s undeniable that solely using organic materials in architectural projects is still far-fetched from the current reality of the ecosystem of today’s construction industry. It isn’t also a coincidence that the co-author of ‘cradle to cradle’ is an architect, which is why the cradle-to-cradle (not cradle to grave) philosophy or an attempt to turn trash into money can be seen in many areas of the architectural industry, such as the Upcycling projects by Assoc.Prof.Dr. Singh Intrachooto based in Thailand. The works Rotor from Belgium have created are also an interesting example in the way they work with the material flow of the construction process to facilitate a network that allows materials to circulate without ending up being thrown away. The endeavor similar to that of Rotor can be seen in a research project called ‘Building As Material Bank’ or BAMB initiated by the European Union. The research questions the amount of leftover materials and the amount of resources used in today’s construction industry.

BAMB works on the concept of a shifted perspective, from looking at buildings as a product constructed, used and eventually demolished when expiration date is reached, to perceiving buildings as a state of materials that is ready to change and enter a new state. With this take, buildings exist as a material bank where materials are kept as a state of a built structure; an actively operated bank so to speak. And when the time comes, the bank is ready to release the materials back into the cycle. Certainly, to achieve such a state isn’t easy. We are more than familiar with the sight of demolished or torn down structures, and while many of the dismantled materials get circulated and reused, it is incredibly difficult to prevent a massive amount of waste from being created. What BAMB is trying to do is designing buildings to be, not a form of product, but a state. In other words, it’s the design that helps stop transformable materials from actually transforming and separate each process from one another.

This particular concept is somewhat known as Design for Disassembly, which looks at the differences between the definition of disassembly and demolition, especially taking a deeper look at the reversible design properties. It’s an approach to architectural design that looks further to the ending, how a building reaches its death (or the beginning of a new life) while still highlighting the independence and exchangeability of its components. The recently renovated Good Cycle Building head office owned by a long-standing Japanese contracting company in Nagoya is one of the examples that pays close attention to materials’ life cycle in the renovation process. The maximized use of leftover construction materials includes the use of earth, which would have been a waste (with extra cost needed for disposing) if it hadn’t been for the design that ended up using the material as the walls’ surface finish. The method was common in the construction of traditional Japanese homes in the past while the earth walls help adjust the humidity of the building’s workspace. The project also incorporates users’ (the company’s employees) participation in the construction process.

Photo: Roland Halbe

From demolition to designing death

The attempt to design a building by considering it as a state doesn’t stop at unifying different materials. The transformation of Sony Building known to most as the Sony Ginza Park should be another example of how a building is perceived and developed as a prolonged cycle. On September 29th, 2021, three years after completing the construction, Sony Ginza Park ceased its operations with the event called ‘Last Day in the Park,’ which included a heart-to-heart conversation between the project’s owner, the teams involved in its existence, and a critic. While the final objective Sony has is to construct a new building, which is expected to be completed in 2024, the process before the inception of the new building takes place was carefully designed with a generous amount of time given in order for everything to be fully realized. Looking back to 2013, a large team of architectural historians, curators and designers from various fields, were extending the demolition process in the hope of allowing people to experience the building under a different state.

In 2016, before the scheduled demolition took place, the building was opened to house a concept store called ‘Park-ing Ginza’. Meanwhile, throughout the three years of its operation, Ginza Sony Park offered a chance for people to be introduced and bid farewell to the old building, and at the same time, it functioned as a place where data indicating users’ behaviors was collected from their experiences of using the building’s physical space as well as its virtual state. All of these experiences were taking place, and all the while the building was also doing its job in promoting and rebranding Sony. Undoubtedly, questions that were raised about why the building needed to go down, or whether eliminating renovation as a viable option was really the right decision, still remain at the back of many people’s minds. But at the very least, one can say that Sony Building’s death was an honorable one. The demolition process was designed and recognized for its importance by the people who truly acknowledge the values of its existence in both the physical aspect and the more abstract dimensions such as its behaviors as a work of architecture. Parts of the facade were carefully treated and turned into thoughtfully designed souvenirs, somewhat similar to a remembrance of the dead. The nature of the building as a public building, which was the essence of the old Sony Building, gets passed on to the work ‘Park,’ which has been gradually reconciled and interpreted through different states of the building.

We actually want to look at the entire operation as both a rebranding and a promotion of the brand and the new building, which makes use of every part and level of the process. Such a perception does not only question the demolition and reconstruction process, but also the time and design method, which would normally be rather limited (considering the building’s age) and would leave no room for experimentation. One can say that this is how a building’s death is designed, so that its past life and existence can help determine the typology and behaviors of the newly conceived architecture. Bringing our attention back to Thailand where in recently passed November, the Scala Theater’s building was torn down, and its departure has sparked many to contemplate over whether that was the best death Scala could receive. A sustainable way out would never be possible without sincere cooperation from many parties, especially from the owner with a clear vision and an open mind.

Silkii moma pavilion mirror

by Neri OxmanExperiments robotic silk deposition

by Neri Oxman

Outro

Those who were growing up in Thailand during the 1990s would probably still remember being taught that using products that are made from wood was a cause of deforestation. I still remember when I first moved to Japan, the school was teaching us how using wooden products was actually a way of saving the forest. I recall feeling perplexed about how the two countries had such starkly different mindsets. Surely, it was because the two contexts in which wood was being addressed refer to two different types of wood with significantly different growing rates. Not only that, the two mindsets were looking at two entirely different cycles, socioeconomic issues including the ways the material was used to answer to two dissimilar systems.

Even concrete, which is often branded as a stigma of Modernism, is now being supported by several researches about the possibility of it being an excellent carbon capturer. The progressiveness of how architects work with the ‘return concept’ as well as concrete recycling can help reshape the norms and values of this very plastic material in the near future. Vice versa, the research done on wood and other organic materials in the few recent years can essentially open unchartered territory and create a new ecosystem for the construction industry. The actual point, however, is asking yourself what does your version of ‘Circular’ include? What is the actual word you would identify as the prefix for it? Many critics have raised concern about the circular concept having its own danger, for it’s an idea based on a hypothesis where we can think of things as ‘Circular’. But can we really? Especially when there’s a possibility for the cycle to be an open instead of a closed system?

Perhaps there is no definite or ready-to-use type of answers to the road to ‘Circular Living’. But what’s really important is that you should be contemplating and questioning things you’re doing or looking at the area you work in. Because no matter how many trees you grow and ‘organic materials’ you use, they can all end up being green washed or social washed without careful thinking, consideration, and true understanding and cooperation by those involved. Like many people have said, continuous action is the answer, because the journey to circular living, today, in this country, is going to be a long one.