‘Skin’ or ‘Shell’ are often associated with superficiality or shallowness. Expressions that illustrate this point include, skin-deep knowledge or an empty shell of a human being. But in reality, the skin or shell, whether of humans or fruits, have significant roles, ones that cannot be disconnected from their existences. Imagine a durian without its spiky husk, or a banana or an apple without any skin. The thickness, rigidity, textural characteristics or even chemical compounds, colors, forms and structures all function collectively and indivisibly with the content and essence. Architecture is similar in that sense. The shell serves, not only to protect what’s inside, but as an interface that allows a building to communicate with the outside world. It acts as a sensory receptor that perceives and conveys information, transfers heat, humidity, energy and at times even contributes as a supporting composition.

Text: Pornpas Siricururatana, Ph.D.

Photo courtesy of Beer Singnoi Foto_momo , L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui, Professor Ruekdee Phowanakul’s, Harunori Noda *Gankohsha, Philip Ruault except as noted

Download the online journal Issue 02 More Than Skin Click here

คำว่าผิว หรือเปลือก มักถูกใช้ในทำนองว่าไม่มีแก่นสารไม่ลึกซึ้ง ไม่ว่าจะเป็นรู้แบบผิวๆ คบแบบผิวๆ มีแต่เปลือก หรืออื่นๆอีกมากมาย แต่ถ้าลองมาคิดดูไม่ว่าผิวคน หรือเปลือกผลไม้ ต่างก็มีหน้าที่อันยิ่งใหญ่ ที่ไม่สามารถตัดขาดจากตัวของมันเองได้ ถ้าทุเรียน กล้วย หรือแอปเปิ้ลไม่มีเปลือก คุณคิดว่ามันจะกลายเป็นอย่างไร ความหนา ความแข็ง ลักษณะของผิวสัมผัส หรือแม้แต่องค์ประกอบทางเคมี สี รูปทรงโครงสร้างของมันล้วนทำงานร่วมกับเนื้อหรือแก่น อย่างยากที่จะแยกออกจากกันได้ สถาปัตยกรรม ก็เช่นเดียวกัน ผิวไม่เพียงทำหน้าที่ห่อหุ้ม ปกป้อง สิ่งที่อยู่ข้างใน แต่ยังทำหน้าที่เป็น interface สื่อสารกับโลกภายนอกเป็นต่อมรับรู้ และถ่ายทอด ข้อมูล ความร้อน ความชื้น พลังงาน หรือแม้แต่เป็นโครงสร้างรองรับตัวมันเองด้วย

Photo: Beer Singnoi, Fotomomo

นักประวัติศาสตร์สถาปัตยกรรม Reyner Banham กล่าวไว้ประมาณว่า เทคโนโลยีอย่างระบบปรับอากาศ หลอดไฟฟลูออเรสเซ้น และวิวัฒนาการทางโครงสร้าง ทำให้สถาปัตยกรรมยุค 1950s ของอเมริกา “หย่า” กับท้องถิ่นและดินฟ้าอากาศ แต่เมื่อมองกลับมาที่ประเทศไทยหรือประเทศในเขตร้อนแบบเราๆ แล้ว กลับกลายเป็นว่า ในขณะที่ curtain wall และระบบปรับอากาศกำลังรุ่งเรืองในสหรัฐอเมริกา รูปแบบอาคารลักษณะหนึ่งได้ถูกพัฒนา แผ่ขยาย และสร้างซ้ำอย่างรวดเร็ว โดยสถาปนิกและวิศวกรที่ทำงานในประเทศที่กำลังก้าวเข้าสังคมหลังอาณานิคมเหล่านี้ โจทย์ของอาคารในประเทศเหล่านี้ ไม่ใช่การเปิดรับแสงอาทิตย์เพื่อแสงสว่างและความอบอุ่น แต่เป็นการต่อสู้กับแสงอาทิตย์ที่แผดเผา พร้อมๆกับการรับมือกับฝนฟ้าและพายุโซนร้อน ในประเทศที่สาธารณูปโภคพื้นฐาน เทคโนโลยี หรือเงินทุน ยังไม่เพียงพอที่จะผลิตคิดค้นระบบปรับอากาศเองได้ และกระจกคุณภาพสูงก็ยังเป็นสินค้านำเข้าที่มีราคาแพง ระบบแผงบังแดดที่มีลักษณะเป็นเลเยอร์ หรืออาจเรียกได้ว่าเป็นผิวที่มีความลึก จึงกลายเป็นทางออกที่น่าสนใจ เพราะนอกจากจะช่วยรับมือกับแสงแดด และปล่อยให้ลมพัดผ่านแล้ว ยังช่วยลดความเป๊ะของการก่อสร้าง ที่เป็น a must ในระบบ Single Glazing หรือพวกหน้าต่างโล้นๆ ที่พึ่งพาความสามารถทุกๆอย่าง ไปที่กระจกและรอยต่อที่เปราะบาง

แน่นอนว่าการแก้ปัญหาของผิวที่เปราะบาง ไม่ใช่โจทย์ใหม่เอี่ยมแกะกล่อง วิธีการจัดการกับปัญหาเก่าแก่นี้ จริงๆแล้วก็ทำได้อย่างที่เรารู้กันดีจากอาคารพื้นถิ่นในภูมิภาค ไม่ว่าจะเป็นการใช้หลังคาหรือชายคา เข้ามาปกป้องผิวเหล่านี้ หรือการทำงานร่วมกับพื้นที่ภายนอก จัดวางพื้นที่แบบ in between สอดแทรกเข้าไป เพื่อรับมือกับแดด ลม ฝน และสิ่งแวดล้อมอื่นๆ แต่เมื่อหลังคาแบบพื้นถิ่น หรือหลังคารูปแบบต่างๆ ถูกโยงกับความหมายทางสังคมที่ไม่เป็นที่ต้องการ และความหนาแน่นของพื้นที่ก็เริ่มสูงเกินกว่าที่จะตอบโจทย์ในแบบหลังได้อีก กลไกของระบบแผงกันแดด หรือที่เรียกกันว่า Brise Soleil นี้ จึงกลายเป็นทางเลือกที่เห็นได้ในทุกๆมุมโลก โดยเฉพาะอย่างยิ่งในประเทศกลุ่ม Global South ในยุคหลังอาณานิคม ไม่ว่าจะโดยคนในประเทศ หรือนอกประเทศ

Photo: L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui

ในประเทศไทยเอง โดยเฉพาะอย่างยิ่งหลังสงครามโลกครั้งที่สอง อาคารสร้างใหม่จำนวนมากก็ทำงานกับผิวที่มีความลึกพวกนี้ ทั้งอาคารที่ทำการราชการ สถานศึกษา โรงพยาบาล หรืออาคารตึกแถว ซึ่งการทำงานกับผิวที่ว่า ก็ทวีความชัดเจนขึ้นไปอีก ในยุค 60-70 ไม่ว่าจะเพราะอิทธิพลจากวงการสถาปัตยกรรมของโลก หรือจะเพราะบริบทเมืองที่อาคารค่อยๆสูงมากขึ้นก็ดี แม้ว่าไม่กี่ปีที่ผ่านมา อาคารจำนวนมากในยุคนี้จะถูกทุบทิ้งลงอย่างน่าเสียดาย เราน่าจะเคยผ่านตากับอาคารเหล่านี้บ้าง ไม่ว่าจะในชีวิตจริง หรือผ่านสื่ออย่าง fotomomo และกระแสอนุรักษ์อาคารต่างๆ

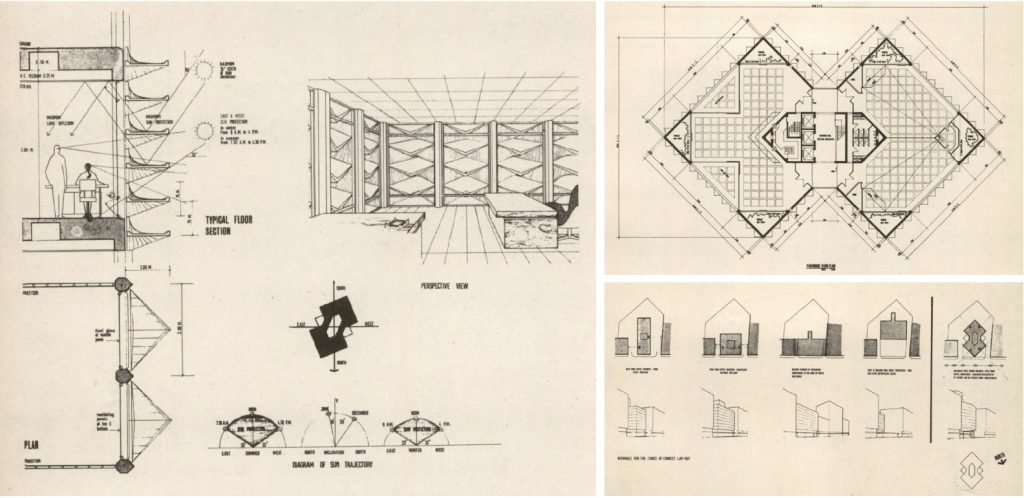

อาคารอย่าง ธนาคารกรุงไทย สาขาสวนมะลิ (อาคารธนาคารไทยพัฒนาเก่า) ผลงานของคุณอมร ศรีวงศ์ ร่วมกับคุณรชฎ กาญจนะวณิชย์ ยังคงดูทันสมัยแม้เวลาผ่านมากว่าห้าสิบปีแล้ว facade ที่ดูซับซ้อน จริงๆแล้วมาจากชิ้นส่วน precast concrete เพียงหนึ่งชนิด ที่ทำหน้าที่ร่วมกับโครงสร้างแบบแขวน ได้อย่างผสมผสาน หรือ อาคารศรีเฟื่องฟุ้ง (อาคารคาเธ่ย์ทรัสต์เก่า) ที่ใช้ HP shell precast ขนาดจิ๋ว มากกว่าสามพันอัน ติดตั้งโดยรอบ เพื่อเป็นตัวกรองแสงแดด และปกป้องผนังกระจกโล้นๆ ที่ติดตั้งระหว่างเสา เช่นเดียวกับอาคารไทยพัฒนาเก่า สิ่งที่น่าสนใจของอาคารคาเธ่ย์ทรัสต์ คือกลไกเบื้องหลังของ”ผิว”เหล่านี้ ไม่ว่าจะเป็นขนาดของ mini shell ที่ทำงานสอดคล้องกับระยะช่วงเสาที่ถูกดันออกมาที่ขอบอาคาร ด้วยระบบโครงสร้างแบบ Diagrid Slab ซึ่งว่ากันว่าก่อสร้างยากมาก และผังอาคาร ที่เป็นสี่เหลี่ยมจตุรัสหมุน 45 องศา ซ้อนกันสองชิ้น ซึ่งช่วยลดพื้นที่ circulation ในการให้เช่าได้มาก ภาพร่างของผู้ออกแบบจากสำนักงานสถาปนิกอินทาเรน ทำให้เราเห็นร่องรอยของความคิดและความพยายามในการคำนวณ การทำงานกับแสงอาทิตย์และพื้นที่โดยรอบ

Photo: Beer Singnoi, Fotomomo

Not only was it a potential solution that could help buildings handle excessive sunlight and maximize natural ventilation, it lessened the need for the precision of the construction.

อาจกล่าวได้ว่า ยุค ’80s เป็นยุค ที่การเงินและการลงทุนเริ่มก้าวมานำหน้าเหนือสิ่งอื่นๆอย่างชัดเจน ความต้องการที่จะขายหน้าตา ภาพลักษณ์ ดึง form ออกมาจาก force (โครงสร้าง) และ flow (พลังงานและสิ่งแวดล้อม) ที่เคยถูกพยายามให้ทำงานร่วมกัน ความต้องการในการควบคุมสภาวะแวดล้อมในอาคาร จากมลภาวะภายนอก ผลักให้งานระบบพัฒนาขึ้น และราคาถูกลงอย่างรวดเร็ว ในขณะที่กระแส postmodern ก็เป็นแรงถีบให้ความหมายเชิงสัญลักษณ์ เขยิบลำดับความสำคัญขึ้นมาเป็นอันดันต้นๆ สเกลของอาคารที่มีขนาดใหญ่ขึ้นเรื่อยๆ ก็เป็นแรงดันอีกส่วน ที่ทำให้เกิดการแตกกลุ่มย่อยของความเชี่ยวชาญ การทำงานร่วมกันแบบผสมผสานระหว่างสถาปนิก วิศวกร และทีมก่อสร้างที่เห็นได้ในยุคก่อนหน้า เริ่มเห็นได้ยากขึ้น ความหมายเริ่มถูกตัดขาดจากถิ่นที่และระบบการก่อสร้าง

กดปุ่ม fast forward เร็วๆ กลับมาที่โลกสถาปัตยกรรมช่วง 10-20 ปีมานี้ ถิ่นที่และท้องฟ้าอากาศ วัฒนธรรมและบริบท โครงสร้างและระบบการก่อสร้าง ถูกนำมาปัดฝุ่น และพัฒนาอย่างก้าวกระโดด ภายใต้แรงสนับสนุนและผลักดันจากกระแส computerization และ digitization ที่กลับมาเชื่อมการทำงานระหว่างกลุ่มความเชี่ยวชาญพร้อมๆกับทำให้ความสามารถในการคำนวนทางโครงสร้าง การพัฒนาของวัสดุ และกระบวนการก่อสร้างใหม่ๆก้าวไปในอีกระดับ Pluralism ของ postmodern ที่ยังติดกับดักภาพลักษณ์ที่ตายตัว ถูกคลี่คลายและพัฒนาพร้อมๆกับ tectonic ornamentation ที่ถูกพัฒนาอย่างก้าวกระโดด

Photo: A+E+C, 1976 (from Professor Ruekdee Phowanakul’s archive)

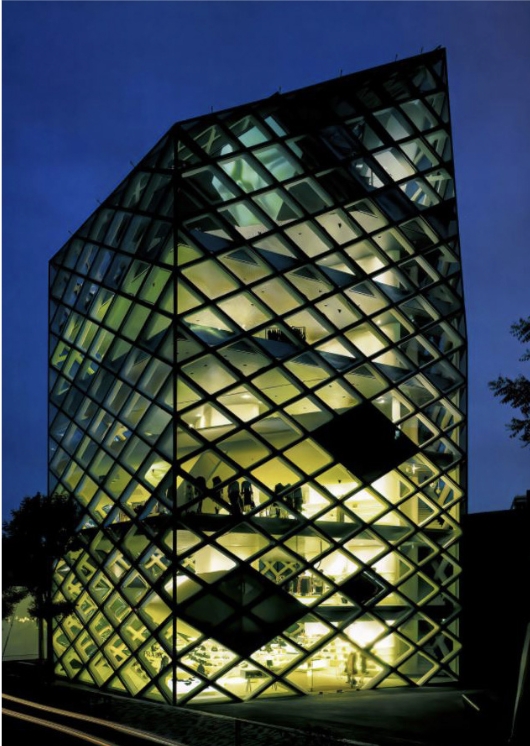

อาคาร Flagship store จำนวนมาก ในย่านการค้า Aoyama Ginza หรือ Omotesando เป็นเหมือนโชว์เคสของอาคาร more than skin เหล่านี้ มาตั้งแต่ช่วงปี 2000s ไม่ว่าจะเป็น Prada ของ Herzog de Mouron ที่บูรณาการโครงสร้าง พื้นที่ และ façade เข้าด้วยกันอย่างแยกออกไม่ได้ Tube แนวนอนที่พุ่งทะลุอาคาร ทำหน้าที่เป็นทั้งโครงสร้าง façade และ “ห้อง” ไปพร้อมๆกัน หรือ Dior ของ SANAA ที่ Omotesandoที่แม้ว่าจะไม่ได้ทำงานกับโครงสร้างเป็นพิเศษ แต่ก็เป็น façade ที่ทำงานกับกระบวนการสร้างและbrand ของ Dior อย่างละเอียดอ่อน façade โปร่งแสง สีขาว คล้ายม่าน ดูพริ้วและนุ่ม ทั้งๆที่ทำจากอคริลิคที่ติดตายตัว มันคือความพริ้วที่เกิดจากการทำงานระหว่างความโค้งของแผ่นอคริลิก และแพทเทิร์นของ ceramic print โปร่งแสง สีขาวที่ถูกปริ้นท์บนอคริลิกก่อนทำให้โค้ง ความโค้งและความโปร่งแสงหลายระดับนี้ทำงานร่วมกับแสงจนเกิดปรากฏการณ์ที่ไดนามิค ที่ทั้งนุ่มและพลิ้วอย่างที่เราเห็น อาคาร Louis Vuitton หลายๆสาขาโดย Jun Aoki ก็เป็นชุดอาคารที่ให้ความสำคัญกับผิวที่ทำงานกับสภาวะแวดล้อมที่ Dynamic เหล่านี้เช่นเดียวกัน สาขาล่าสุดที่ Ginza ในชื่อออฟฟิสใหม่ AS น่าจะเป็นตัวอย่างที่ดีที่โปรเจคทีม สามารถนำพัฒนาการของวัสดุทั้งเทคนิคการ Coating การผลิตกระจกโค้งสามมิติ รวมถึงกระบวนการผลิตชิ้นส่วนอลูมิเนียมซัพพอร์ต มาทำงานร่วมกัน เพื่อตอบโจทย์ที่ซับซ้อนได้ (หนึ่งในนั้น คือความเป็นเสาจากน้ำทะเล ระลึกถึง Ginza ในสมัยเอโดะ ที่ยังเป็นแหลมยื่นไปในทะเล!)

สิ่งหนึ่งที่เชื่อมอาคารเหล่านี้เข้าด้วยกัน นอกจากความพยายามทำงานกับกระบวนการสร้าง และวัสดุที่ละเอียดอ่อนและพิถีพิถันของทั้งโปรเจกทีม ไม่ว่าจะเป็นสถาปนิก วิศวกร และทุกๆคนในกระบวนการสร้างแล้ว แน่นอนว่าสิ่งที่ขาดไม่ได้เลย คือความเป็น Flagship store ของ brand high-end ที่มีเงินทุนหนา และเทคโนโลยีการคำนวนและการก่อสร้างขั้นสูง ก็เป็นปัจจัยสำคัญที่เปิดโอกาสให้อาคารที่มีความซับซ้อนสูงมากๆเหล่านี้ เกิดขึ้นได้ แม้ว่าหลัง Hamburger Crisis อาคารลักษณะนี้อาจจะมีให้เราเห็นน้อยลงไปบ้าง แต่ก็ไม่ได้หายไปเลย การทำงานร่วมกับวัสดุและกระบวนการสร้าง หรือการทำงานของวัสดุ กับสภาวะแวดล้อม ยังคงเป็น theme อมตะ ของสถาปนิกและวิศวกร ในบริบทที่หลากหลาย ในประเทศไทยเอง ผลงานหลายๆชิ้น ของ studiomake หรือ โปรเจคอย่าง MAIIAM ของ all(zone) น่าจะเป็นตัวอย่างที่ทำให้เห็นการทำงานในลักษณะดังกล่าวในบริบทที่แตกต่างอย่างเมืองไทยได้เป็นอย่างดี ในสภาวะที่ระบบนิเวศของการก่อสร้าง ไม่ว่าจะเป็นวัสดุ ทักษะ ไปจนถึงเงินทุนมีความแตกต่างไปมาก โจทย์ทางวัสดุถูกขยายออกไปถึงที่มาที่ไปและกระบวนการได้มาซึ่งวัสดุนั้นๆ

Prada Aoyama – Herzog de Mouron

Photo: Shinkenchiku 2003.09Dior Omotesando – SANAA

Photo: Shinkenchiku 2004.01Louis Vuitton Ginza Namiki – Jun Aoki and Peter Marino

Photo: Daici Ano

การตอบโจทย์สิ่งแวดล้อมก็ถูกพัฒนาไปมากเช่นกัน เทคโนโลยี simulation ต่างๆ ทำให้เราก้าวเข้าสู่การคำนวนแบบ non-linear ที่ไดนามิค พร้อมๆกับที่คำอย่าง sustainability หรือ resilience ที่ก้าวขึ้นมาเป็นคีย์เวิร์ดหลักของสังคม อาคารสำนักงานขนาดย่อม อย่าง Coop Kyozai Plaza โดย Nikken Sekkei เป็นอีกตัวอย่างของความพยายามนี้ โครงสร้างคานแบบกลับหัวที่ใช้ในโครงการ นอกจากจะทำให้พื้นที่อาคารภายใน ไม่ต้องมีฝ้าแล้ว เพราะจากเหตุการณ์แผ่นดินไหวหลายๆครั้ง ทำให้เรารู้ว่า ฝ้า และ sub-structure เป็นสาเหตุหลักอย่างหนึ่งของอุบัติเหตุที่เกิดขึ้นระหว่างภัยจากแผ่นดินไหว ยังเป็นพื้นที่เก็บอุปกรณ์ต่างๆ สำหรับการป้องกันภัยพิบัติ และทำให้พื้น slab ภายนอกอาคารที่เต็มไปด้วยต้นไม้คงความบางไว้ได้ ระบบ Bioskin หรือ การปล่อยน้ำผ่านท่อเซรามิคภายนอกอาคาร เพื่อให้การระเหยของน้ำช่วยลดอุณหภูมิรอบๆ ถูกนำมาทำให้ เรียบง่าย โดยการติดตั้งโซ่ช่วยระบายน้ำฝนรอบอาคารและการเลือกต้นไม้ที่พิถีพิถัน Bioskin แบบโลเทคนี้ ทำงานร่วมกับ พฤติกรรมของต้นไม้ต่างๆ ซึ่งไม่เพียงช่วยปรับสภาวะแวดล้อมของพื้นที่อาคารด้านในของตัวมันเอง แต่ยังมีส่วนช่วยลดอุณหภูมิของพื้นที่ในระดับย่าน และบรรเทาปัญหาเกาะความร้อนของเมืองอีกด้วย โดยล่าสุด Nikken Sekkei นำหลักการของ Bioskin มาทำงานกับอิฐดินเผาบ้านเรา ภายใต้ชื่องาน ศาลาคอย(ล์)เย็น และจัดแสดงในงาน Bangkok Design Week ที่ผ่านมา

กระแสสำคัญอีกอย่างที่มาพร้อมๆกับโจทย์สิ่งแวดล้อม คงหนีไม่พ้นการเข้าไปทำงานกับผิวอาคารเก่า เพื่อเพิ่มประสิทธิภาพและฟื้นฟูพื้นที่ของอาคารเก่า วิธีการทำงานกับผิวอาคารเก่าของ Lacaton & Vassal โดยเฉพาะอย่างยิ่ง ชุดโครงการ Transform อาคารพักอาศัยเก่าในยุค 60s จำนวนกว่า 500 อาคาร โดยการ insert ผิว หรืออาจจะควรเรียกว่า balcony unit เข้าไปบนผิวเดิมนั้นเป็นจุดเปลี่ยนแปลงที่สำคัญของวาทกรรม ผิว-แก่น ที่ถูกถกมายาวนาน ผิวที่เคยถูกดูแคลน (เป็นระยะๆ) ในโลกของการสร้างอาคารใหม่ ถูกพลิกกลับในโลกของการทำงานกับอาคารเก่า ที่การจำกัดพื้นที่การทำงานมีความสำคัญยิ่ง ในโลกที่ความหมายไม่ใช่สิ่งที่ตายตัวอีกต่อไป ผิวที่ถูกถามหาคงไม่ใช่ผิวที่เป็นสื่อในการถ่ายทอดภาพลักษณ์และความหมายเชิงสัญลักษณ์อีกต่อไป แต่เป็นผิวที่มีความยืดหยุ่น ทำงานกับสภาวะแวดล้อมที่เป็นพลวัตและปรับเปลี่ยนได้ตามสถานการณ์ โจทย์ของเราตอนนี้คงไม่หยุดแค่ ผิวที่เป็นมากกว่าผิว ของตัวสถาปัตยกรรมเอง แต่อาจเป็นโจทย์ที่ถามหา ผิว ที่เป็นส่วนหนึ่งของเครือข่ายและกลไกที่ทำงานกับพื้นที่และสังคมภายนอกในระดับ ย่าน เมือง หรือแม้แต่โลก ก็เป็นได้

Photo: Harunori Noda *Gankohsha

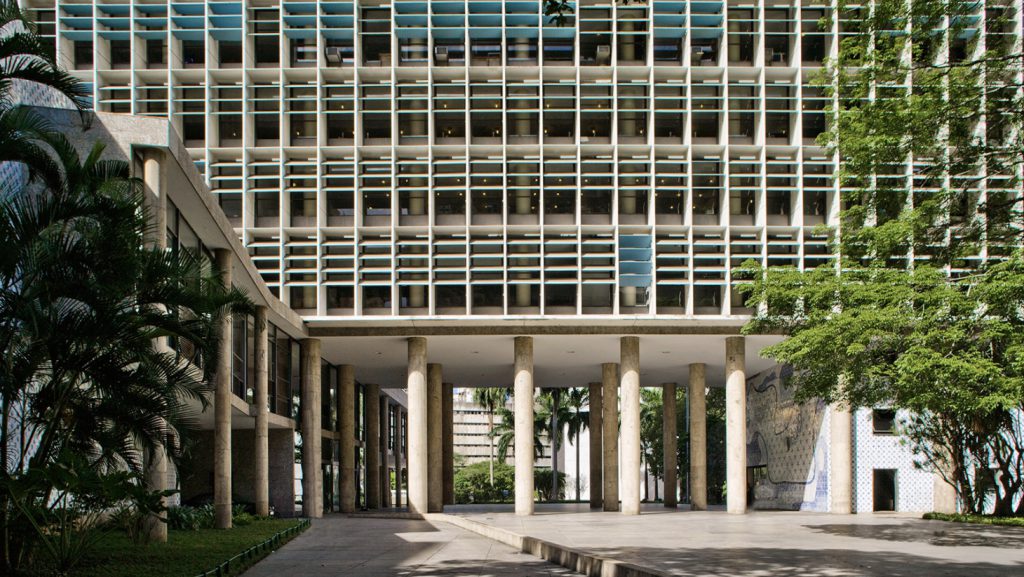

Architectural historian, Reyner Banham, made an argument about how modern technologies such as air conditioning systems, fluorescent bulbs and the structural evolution as a whole had caused American architecture from the 1950s to ‘divorce’ itself from the locality and regional climate. However, looking back at Thailand or other tropical counties, it turns out that while curtain wall and air conditioning systems were seeing their heyday in the United States, another building typology was being developed, and reproduced at such a fast pace by architects and engineers practicing in these countries. What these buildings were required to deliver wasn’t increasing an exposure to sunlight and warm weather, but instead, to battle the glaring natural light with burning temperatures alongside heavy rain and tropical storms. In the counties where basic infrastructure or financial capabilities were still too insufficient to invent and manufacture air conditioning systems, the sun protection panel system with layered skins became an interesting option. Not only was it a potential solution that could help buildings handle excessive sunlight and maximize natural ventilation, it lessened the need for the precision of the construction. This was considered a must in the single glazing system or the frame-less windows and openings that applied all the weight on glass or relatively fragile joints.

Certainly, the attempt to solve these regional problems was far from novel. Several methods have been invented in hopes to find the right solution for this long-standing dilemma. Some can be found in the region’s vernacular architecture, such as the use of a roof structure or canopy to help protect the building’s skin or an integrative approach where outdoor spaces are incorporated as an in-between element that helps a building cope with these climatic conditions. However, especially during the independence movement, vernacular or traditional roof structures became associated with some unwanted social implications. The rise of urban space’s density also made the integrative approach become somewhat luxurious. In these contexts, the mechanism of the sun protection panel system AKA Brise Soleil, has become an alternative adopted in almost every part of the world. Especially in Global South countries during the post-colonial era, by both the locals and outsiders.

Photo: Harunori Noda *Gankohsha

Post World War II Thailand saw a great number of newly built structures, from government, educational to hospital buildings or even shophouses that employed the use of building skins of such depth. Building skins became an even more prominent during the 1960s and 1970s, either because of influences from the global architectural trend or the growing tendency of vertical urban expansion that had caused buildings to become higher. Although many buildings from this particular time period have, unfortunately, been demolished in the past recent years, we have all witnessed their existences first-hand and through medias such as fotomomo, including the rising awareness in architectural conservation.

Buildings such as the Suan Mali branch of Krungthai Bank (the former Thai Pattana Bank’s building) designed by Amorn Sriwong and Rachot Kanchanawanich still looks extremely modern despite the fact that over five decades have passed (Figure.2). The complex-looking facade is made up of only one type of precast concrete part, which works in tandem with the suspension structure. Sri Fueng Foong Building (the old Cathay Trust Building) (Figure.3) uses over 3000 pieces of miniature HP shell precasts by installing them around the architectural structure to help filer the sunlight. It also simultaneously protects the glass panels between column spans. Similar to the old Thai Pattana building, what’s particularly interesting about Cathay Trust’s architecture is the mechanism behind the shells. One of the examples is the size of the mini shells and how they work in accordance to the column spans. These shells are pushed toward the building’s edges using a structural system called Diagrid Slab, which is known to be highly difficult to construct. The building’s layout is made up of two superimposed square masses, twisted to 45 degrees to help lessen the circulation space for maximum rentable spaces. The sketches created by the architect from the Intaren Architecture Office allows us to see traces of ideas as well as attempts to calculate and work with sunlight and the surrounding environment.

ระบบการทำงานกับผิวอาคารเก่า ในโครงการปรับปรุงอาคารที่พักอาศัยรวม

ในยุค ’60 กว่า 500 อาคาร

Photo: Philip Ruaultระบบการทำงานกับผิวอาคารเก่า ในโครงการปรับปรุงอาคารที่พักอาศัยรวม

ในยุค ’60 กว่า 500 อาคาร

Photo: Philip Ruault

In the 1980s when the financial and investment sector saw a significant boom, a desire to market appearance and image, took form out of force (structure) and flow (energy and environment). The demand to control and protect the interior environment from the outside pollution propelled building systems to speedily develop and become cheaper. Meanwhile, the postmodern movement was an influential driving force that glorified the symbolic values of architectural works. Buildings were becoming larger in scale, and the shift led to the ramification of more specialized expertise. The interdisciplinary and collaborative approaches between architects, engineers and the construction team became somewhat of a rarity, while meanings were disconnected from local identity and construction system.

Fast forward to the architecture world in the past 10-20 years, factors such as locality, climate, culture and context, structure and construction system, have been revived with some big progresses and developments driven by the global computerization and digitization phenomena. These trends have been facilitating collaborations between different groups of experts. In doing so it has enabled humans’ ability in structural calculations, material developments as well as new construction methodologies to reach a new level. Postmodern Pluralism, which was once trapped in its own stagnant image, has been reconciled and developed alongside the progressive advancement of tectonic ornamentation.

Several flagship store buildings in Tokyo’s commercial districts such as Aoyama, Ginza or Omotesando have existed as a spectacular showcase of the ‘more than skin’ architecture since the 2000s. The Prada flagship store designed by Herzog de Mouron integrates different elements of structure, building system and façade into an inseparable union (Figure.5). Part of the façade was extruded horizontally, piercing through the building which serves as both the façade’s structure and the tube containing commercial space. Although the façade of the Dior flagship in Omotesando by SANAA (Figure.6), has no specific functional contribution to the structure, it works relatively close and in such a delicate manner to amplify the fashion house’s branding process. The white, translucent façade looks like curtains, wavy and soft despite being made of fixated acrylic mass. The undulating and weightless appearance is made possible by the interaction between the acrylic sheets’ curvy features and the white, translucent ceramic print pattern on the acrylic surface, which was imprinted before the material was bent into the desired form. These multiple layers of curves and translucent surface work together in creating a dynamic phenomenon that makes the façade appear soft and wavy.

Photo: Beer Singnoi, Fotomomo

The Louis Vuitton shops that Jun Aoki has designed are a series of buildings that highlight how building skins work and interact with their dynamic surroundings. The latest branch of the brand, which the architect designed under the new office name, AS, is a great example of how the team was able to incorporate new material developments and coating techniques to build the three-dimensional glass facade that delivers such as a mesmerizing effect. The endeavor included the manufacturing process of the aluminum supporting parts, which were used to help complete the physical and functional details of the complex compositions.

One element that connects these buildings together, in addition to the attempt to deal with the construction process, and the meticulousness of the entire project team from the architects, engineers to everyone involved in the process, is the status of these projects as flagship stores of high-end brands, which came with a hefty budget. All of these aspects coupled with highly advanced building configureration and construction technologies, allowed for the birth of such highly complex buildings to be possible. Although we have seen fewer numbers of buildings of this nature after the Hamburger crisis was over, they have not disappeared entirely. An integrative and collaborative effort between materials and the construction process, or interactions between materials and their surrounding environments, are still timeless themes that architects and engineers go after when Figureuring out ways to work with various contexts of their projects.

In Thailand, many works by studiomake or MAIIAM Museum by all(zone) are interesting examples of this particular approach. In the scenario and context where the elements in the ecosystem of construction, be there materials, skills and budget are starkly different, issues and discussions concerning materials have been extended to the origins and processes from which each material has been obtained.

Photo: Beer Singnoi, Fotomomo

The Challenge lies in the search for new possibilities for the ‘skin’ to be a part of networks and mechanisms that will work and interact with spaces and society on larger scales, from neighborhoods to urban landscapes and even on an earth level.

Environmentally conscious design has also been diligently developed. Simulation technologies have enabled us to utilize more dynamic, non-linear calculation since words such as sustainability or resilience are being more recognized as the society’s keywords. Moderate sized office building, Coop Kyosai Plaza, designed by Nikken Sekkei, is another example of such an endeavor (Figure. 7). The reversed beam structure employed to the design of the project eliminates the need for a ceiling in the interior space. The attempt the get rid of the ceiling actually originated from the previous earthquake incidents in the past, which over time, become a lesson that displayed how ceilings and sub-structures are one of the main causes of accidents during earthquakes. The structure also contains a space that stores disaster prevention equipment while keeping the exterior slabs where the plants are growing physically thin.

The building adopted the mechanism of Bioskin system– a skin of water-filled ceramic pipes which allows the evaporated water to reduce the temperature around the building. Here, the system is simplified by using the rainwater chain instead of ceramic pipes together with a meticulous selection of plants. This somewhat, low-tech Bioskin works together with the plants’ varying behaviors, and collectively helps adjust, not only the interior environment of the building but also the outside temperature of the area as well as the city’s heat-island phenomenon. Nikken Sekkei have recently used the Bioskin principles with Thailand’s locally made red bricks for the Stay Cool Pavilion created and exhibited as a part of the 2021’s Bangkok Design Week.

An equally popular and important trend in line with environmentally friendly design is architects’ attempt to bring life to old buildings by dealing with the existing skins. This process can be witnessed through Lacaton & Vassal’s approach to old building refurbishments, particularly with their Transform series. The refurbishment of over 500-year-old residential structures from the 1960s have been made by adding balcony units to the buildings’ original exterior surfaces. (Figure. 8) It has become a monumental turning point for the long-standing discussions surrounding the shell/core discourse. The shell, as an element that has been looked down upon (from time to time) in the world of newly constructed buildings, gets turned upside down with old buildings where the limitation of usable spaces is a highly crucial factor.

In a world where definitions keep changing, the kind of skin people look for is perhaps not an element with fixed visuals and symbolic implications, but rather, as a flexible aspect with the ability to simultaneously work and interact with the surrounding environment. At the moment, perhaps the challenge lies not just in the physical development of individual architectural skin, but in the search for new possibilities for the ‘skin’ to be a part of networks and mechanisms that will work and interact with spaces and a society on larger scales, from neighborhoods to urban landscapes and even on a global level.