“In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth. And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters. And God said, Let there be light: and there was light. And God saw the light, and it was good; and God divided the light from the darkness.”

Text: Nawanwaj Yudhanahas

ownload the online journal Issue 06 Let There Be Light Click here

“ในปฐมกาล พระเจ้าทรงเนรมิตสร้างฟ้าและแผ่นดิน แผ่นดินก็ร้างและว่างเปล่า ความมืดอยู่เหนือน้ำ และพระวิญญาณของพระเจ้าทรงปกอยู่เหนือน้ำนั้น พระเจ้าตรัสว่า จงเกิดความสว่าง ความสว่างก็เกิดขึ้น พระเจ้าทรงเห็นว่าความสว่างนั้นดี และทรงแยกความสว่างออกจากความมืด”

ประโยคทั้งสี่เริ่มต้นปฐมบทของหนังสือปฐมกาล จากคัมภีร์ไบเบิ้ล บอกเล่ารายละเอียดของเหตุการณ์เมื่อพระเจ้าสร้างโลก อันรวมไปถึงการสร้างมวลมนุษย์ “จงเกิดความสว่าง” คือคำกล่าวที่แสดงถึงพลังแห่งพระเจ้า ผู้รังสรรค์สรรพสิ่ง ได้ตามความต้องการ แต่หากเราตีความ “จงเกิดความสว่าง” ในบริบทของประโยคจากหนังสือปฐมกาลที่ว่า เราอาจมองเห็นคำใบ้ที่ซ่อนตัวอยู่ภายใต้การรับรู้ที่มนุษย์มีต่อแสงสว่าง ไร้รูปร่าง ไม่ชัดเจน และปราศจากนัยยะ ทางศีลธรรมใดๆ แสงสว่างให้กำเนิดสิ่งที่ตรงข้ามกับคุณลักษณะทางกายภาพของมัน นั่นคือความชัดเจน ดีงาม และสิ่งสำคัญที่สุด นั่นคือ ชีวิต

ในปี 2016 Daylight Award ถูกก่อตั้งขึ้นเพื่อเป็นรางวัลแก่สถาปนิก นักออกแบบ นักวิทยาศาสตร์ หรือนักวิจัย ที่สร้างคุณูปการต่อการวิจัยหรือออกแบบแสงธรรมชาติที่ส่งผลต่อสุขภาพและคุณภาพชีวิตของมนุษย์ และสังคม จากหนังสือแห่งปฐมกาลจวบจนปัจจุบัน แสงสว่างยังคงเป็นสิ่งที่ถูกรับรู้ในฐานะตัวแทนของความดีงาม และเกี่ยวพันกับชีวิตและความเป็นอยู่ของเรา แต่อะไรที่ทำให้แสงสว่างในงานสถาปัตยกรรมเป็นสิ่งที่จับใจเหล่าสถาปนิก

เมื่อความตายกลับกลายเป็นชีวิต

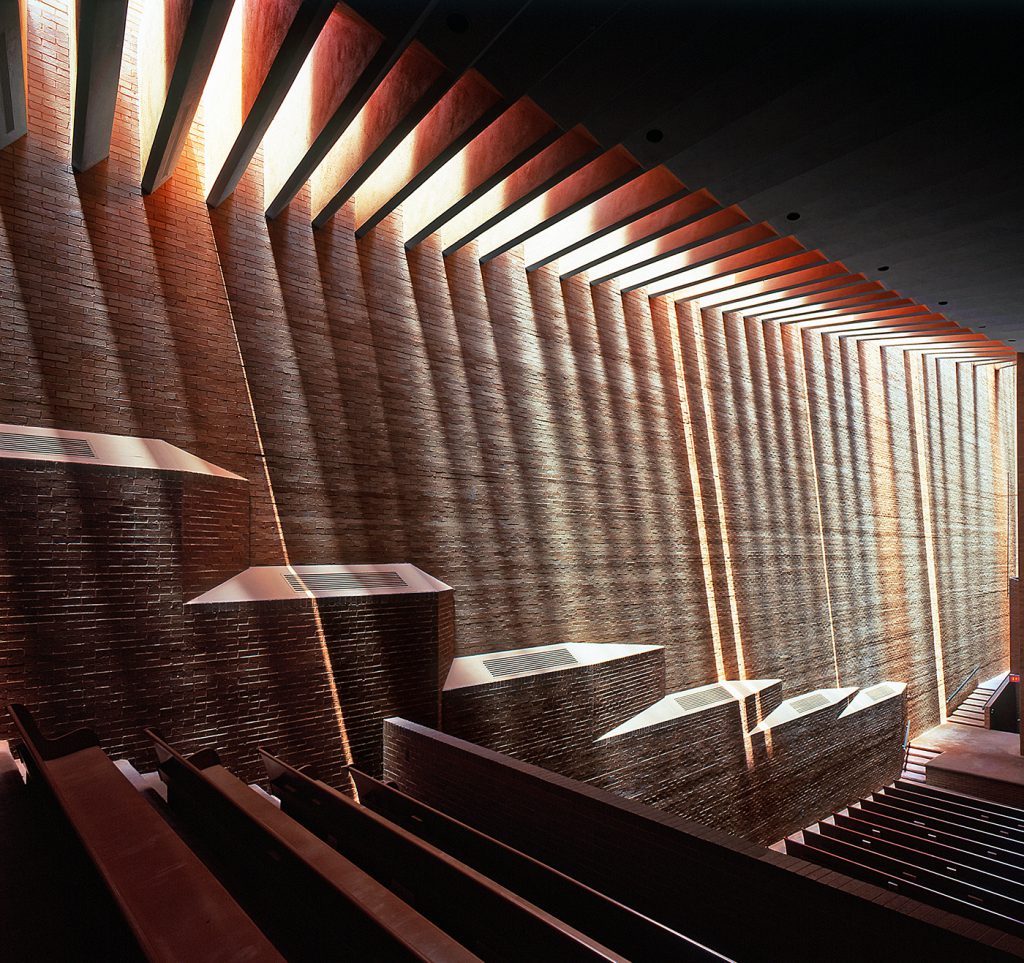

สำหรับปี 2020 รางวัลพิเศษอย่าง Lifetime Achievement Award ถูกเพิ่มเข้าไปในโปรแกรมการแจกรางวัลโดยเฉพาะ Henry Plummer ศาสตราจารย์ด้านประวัติศาสตร์สถาปัตยกรรมและนักถ่ายภาพงานสถาปัตยกรรม เป็นผู้ถูกรับเลือกให้รับแรงวัลนี้เป็นคนแรก ในงานวิจัยของเขา Plummer กล่าวว่าอาคารนั้นคือวัตถุที่มีความหยุดนิ่ง ดังคำที่เขาใช้เรียกมันว่า ‘มวลปริมาตรที่ตายแล้ว’ นั้นปรากฏสัญญาณของการมีชีวิต ไม่เพียงจากการเข้ามาใช้งานของผู้คน แต่ด้วยการปรากฏตัวของแสงส่องเข้ามาในห้องๆหนึ่ง หรือทอดตัวผ่านพื้นผิวของกำแพง พูดอีกนัยหนึ่ง สถาปัตยกรรมนั้นแปรเปลี่ยน เคลื่อนไหว และมีชีวิตได้ ก็เมื่อแสงธรรมชาติเข้ามาเป็นส่วนหนึ่งของการมีอยู่ของมัน

หากลองก้าวออกมาจากสถาปัตยกรรม เข้าสู่เขตแดนของศิลปะดูสักชั่วขณะ เพื่อสำรวจตรวจตราว่าอาคารต่างๆถูกทำให้มีชีวิตขึ้นมาได้อย่างไร ศิลปินแห่งชาติชาวไทย ปรีชา เถาทอง นั้นเป็นที่รู้จักอย่างกว้างขวางจากผลงานภาพเขียนอาคารวัดวาอารามภายใต้ปรากฏการณ์แสงจากดวงอาทิตย์ อาคารวัดที่ถูกทำให้สว่างไสวขึ้นด้วยแสงแดด ถูกขับเน้นและตีกรอบด้วยอีกองค์ประกอบหนึ่งของอาคารภายใต้เงามืด องค์ประกอบทางสถาปัตยกรรมที่วางตัวอยู่ภายนอกผืนผ้าใบ สร้างเงาพาดผ่านลงบนภาพวาดจิตรกรรมฝาผนัง ตัดกันกับอีกส่วนหนึ่งของงานจิตกรรมชิ้นเดียวกันที่ปรากฏตัวอยู่อย่างสดใสด้วยพลังของแสงที่พาดผ่าน มิติของความลึกที่แตกต่างกันไปของอาคารถูกขับเน้น ในขณะที่ปริมาตรบางส่วนโดดเด่นขึ้นภายใต้แสงอาทิตย์ อีกส่วนถูกบดบังด้วยอิทธิพลของเงา

อาคารวัดถูกอาบด้วยแสงโทนเหลืองของพระอาทิตย์ยามเช้า หรือเปล่งประกายท่ามกลางสีเข้มของท้องฟ้าเวลาพลบค่ำ งานจิตรกรรมของเขาจับภาพของสภาวะที่ปรากฏให้เห็นราวกับว่าชั่วขณะหนึ่งเวลาได้หยุดหมุนลง สถาปัตยกรรม หรือ ‘วัตถุไร้เสียง’ ดังที่ Plummer เรียก เปลี่ยนแปลงไปตามโมงยามของวัน จากการมีอยู่ของแสงอาทิตย์ ปรีชา เถาทอง บอกเล่าถึงการสร้างงานศิลปะของเขาว่า แสงเดินทางอย่างไม่มีจุดสิ้นสุด เว้นเสียแต่ว่าเส้นทางของมันจะถูกกีดกั้นด้วย “ตัวกลาง” บางอย่างถ้าเป็นเช่นนั้น ในฐานะของผู้ออกแบบ อะไรคือหนทางที่จะสร้างสรรค์ “ตัวกลาง” ที่จะก่อให้เกิดการมีอิทธิพล ซึ่งกันและกันในรูปแบบที่ว่า

ก้อนบล็อค

ยังเป็นที่ถกเถียงกันว่าความโปร่งใสเป็นหนึ่งในหัวข้อที่ได้รับการพูดถึงมากที่สุดในประวัติศาสตร์สถาปัตยกรรม นับตั้งแต่อารยธรรมโบราณ เราได้เห็นการเจาะรูกำแพงที่มีมวลแข็งตันเพื่อนำเอาแสงธรรมชาติเข้าสู่พื้นที่ภายใน การค้นพบเทคนิคการก่อสร้างสำคัญดังกล่าวเกิดขึ้นในช่วงของความเคลื่อนไหวของแนวคิดสถาปัตยกรรมโมเดิร์นที่เราได้เห็นภาพหน้าต่างหรือกำแพงใสที่สูงจากพื้นจรดเพดาน และพื้นที่ภายในเรียบนิ่งที่เปี่ยมล้นไปด้วยแสงธรรมชาติ แต่การคลุมด้านข้างของอาคารด้วยผืนกระจกขนาดใหญ่นั้นไม่ใช้หนทางเดียวในการออกแบบ ‘ตัวกลาง’ ในยุคสมัยดังกล่าว เช่น ในปี 1932 Pierre Chareau และ Bernard Bijvoet ห่อหุ้มบ้านสามชั้นในปารีสที่พวกเขาออกแบบด้วยบล็อคแก้วโปร่งแสง Maison de Verre ที่มีความหมายแปลได้ว่าบ้านแห่งแก้ว ประกอบขึ้นจากพื้นที่โถงโปร่งสูงสองชั้น ที่สว่างไปด้วยแสงที่กระจายอย่างทั่วถึง คุณลักษณะดังกล่าวอาจดูเป็นสิ่งที่พบเห็นได้ทั่วไปในงานออกแบบสถาปัตยกรรม ในปัจจุบัน แต่การปรากฏขึ้นของมันในช่วงปีทศวรรษ 1930 ทำให้มันเป็นองค์ประกอบที่ความต่างและบุกเบิกมากพอดู ก่อนที่มันจะกลายมาเป็นลักษณะของการใช้แสงในงานสถาปัตยกรรมที่อยู่อาศัยที่ได้รับความนิยมข้ามยุคสมัยมาจวบจน ปัจจุบัน

ย้อนกลับไปเมื่อแปดสิบปีที่แล้วในโตเกียว ฟาซาด (Façade) ที่สร้างขึ้นจากบล็อคแก้วขนาดเท่าก้อนอิฐ ถูกนำมาใช้กับงานอย่าง Optical Glass House โดย Hiroshi Nakamura & NAP ด้วยที่ตั้งที่อยู่ติดกับถนนที่มีความจอแจ ความท้าทายของงานออกแบบบ้านหลังนี้ คือการปิดกั้นการรบกวนของเสียงโดยรอบ หากแต่ยังหยิบยื่นเข้าถึงวิวและแสงธรรมชาติอยู่ ด้านหลังฟาซาดขนาด 8.6 x 8.6 เมตร คือ สวนที่ปลูกต้นแอช เมเปิ้ล และฮอลลี่ สถาปนิกได้บรรยายถึงผลลัพธ์รูปแบบต่างๆ ของแสงที่เกิดขึ้นจากการผสมผสานและปฏิสัมพันธ์ระหว่างบล็อคแก้วและต้นไม้ แสงที่ผ่านการกรองกระจายตัวอยู่ท่ามกลางพื้นที่ ส่องประกายระยิบระยับอยู่ภายในคอร์ทยาร์ด ลวดลายเคลื่อนไหวราวกับแสงและเงาเต้นระบำอยู่บนพื้น การหยอกล้อกันระหว่างแสงและสถาปัตยกรรมนั้น เกิดขึ้นจากการที่สถาปนิกวางเอาบ่อน้ำที่มีหน้าที่ของการเป็นช่องแสง บนหลังคาไว้ด้านบนของทางเข้า ที่บริเวณนี้ พลังงานของแสงและน้ำทำงานร่วมกัน และก่อเกิดเป็นลวดลายของแสง ที่กระพริบเป็นประกายบนพื้น ต้อนรับผู้มาเยือน และบอกให้เจ้าของบ้านที่กำลังจะออกไปข้างนอกรู้ถึงสภาพอากาศในแต่ละวัน ไม่ว่าน้ำจะนิ่ง เคลื่อนไหวเบาๆ จากการถูกลมกระทบ หรือส่งเสียงเปาะแปะยามฝนตก ลวดลายของแสงก็จะปรากฏให้เห็นตามมาเสมอ สถาปนิกออกแบบ “ตัวกลาง” เพื่อช่วยให้ผู้อยู่อาศัยได้ใช้ชีวิตไปพร้อมๆ กับการรับรู้ถึงฤดูกาลที่เปลี่ยนแปลง ผ่านแสงธรรมชาติระหว่างวันที่ผันแปรไปในแต่ละช่วงเวลา

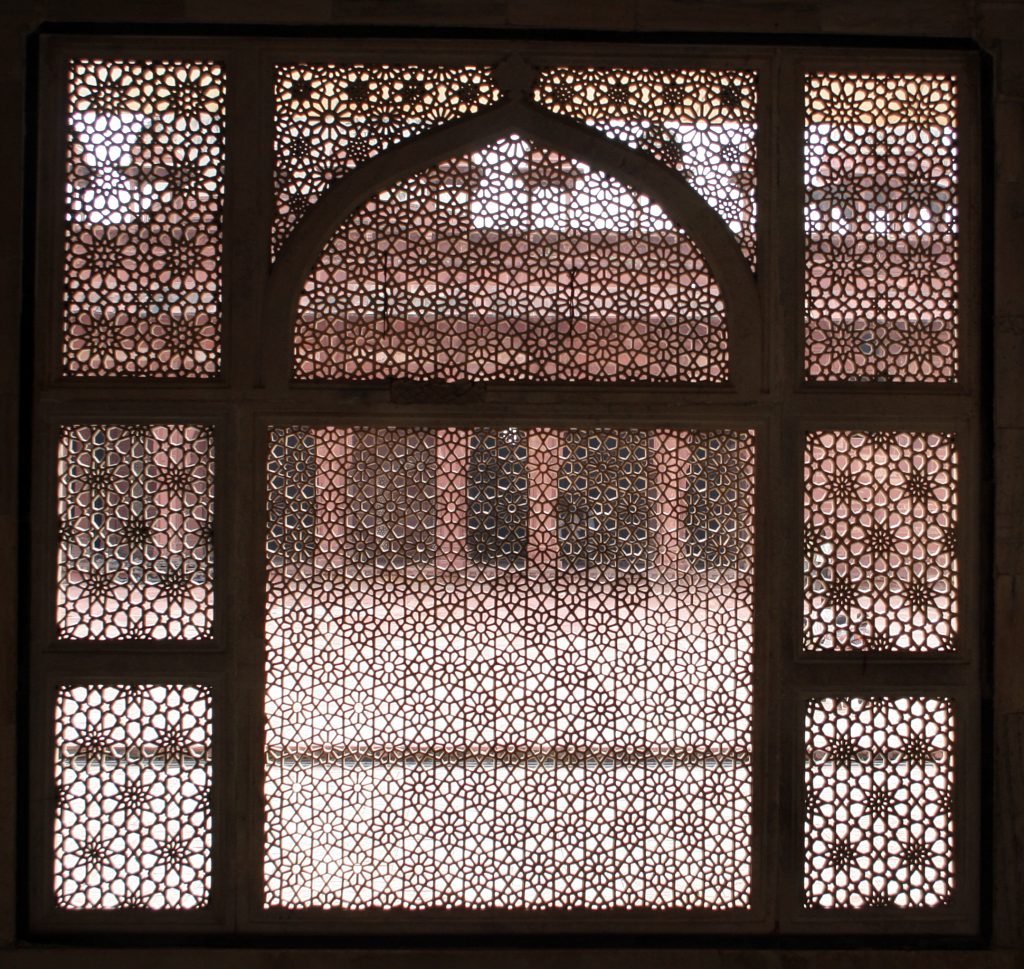

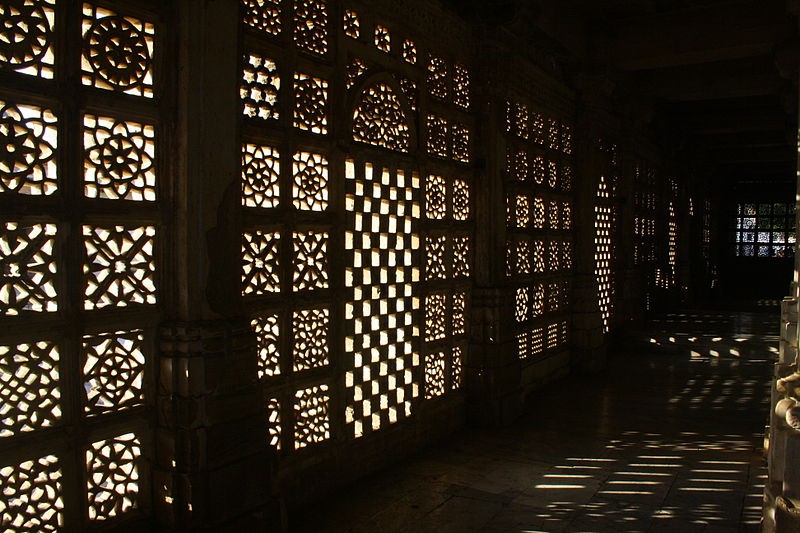

ตัวกรอง

แสงธรรมชาติเป็นสิ่งที่เหล่ามนุษย์ผู้ใช้อาคารชื่นชอบปรารถนาอยู่แล้วด้วยสัญชาตญาณ แต่ในภูมิอากาศที่แสงอาทิตย์แผดเผารุนแรง อะไรคือหนทางที่จะออกแบบ ‘ตัวกลาง’ เพื่อรองรับสิ่งแวดล้อมดังกล่าว แผงช่องลมหรือ Jali ในภาษาอินเดีย หรือ Mashrabiyya แห่งดินแดนแถบตะวันออกกลางเป็นองค์ประกอบหนึ่งของสถาปัตยกรรมพื้นถิ่นที่ช่วยลดความรุนแรงเข้มข้นของแสงอาทิตย์ทั้งความร้อนและจ้าที่มาพร้อมกับแสงแดดลวดลายเรขาคณิตที่ถูกสร้างขึ้นให้มีคุณลักษณะเชิงตกแต่งไม่ได้ให้คุณค่าในทางสุนทรียะแต่เพียงอย่างเดียวหากแต่ยังมีประโยชน์ด้านการใช้สอยอย่างการระบายอากาศอย่างมีประสิทธิภาพอีกด้วย

บางทีสถาปนิกJean Nouvel อาจจะได้ให้การตีความที่ร่วมสมัยของความรู้ที่มีอยู่อย่างยาวนานนี้ไว้แล้วก็เป็นได้ ในงานอย่าง Louvre Abu Dhabi แสงธรรมชาติถูกกรองผ่านชั้นโครงตาข่ายสแตนเลสและอลูมิเนียมอันซับซ้อน แต้มแต่งพื้นของพิพิธภัณฑ์อย่างมีพลวัต เบื้องหลังผลลัพธ์ดังกล่าว คือโครงสร้างโดมเจาะช่องแสงกว้าง 180 เมตรที่พาดตัวอยู่เบื้องบน ราวกับว่า Jali ขนาดใหญ่ยักษ์ได้ถูกแปรสภาพจากกำแพงไปเป็นเพดาน สิ่งที่ได้คือองค์ประกอบแสนมหัศจรรย์ ที่ปรากฏอยู่ราวกับเป็นส่วนหนึ่งของดินแดนท้องฟ้าเบื้องบน และยึดโยงอยู่กับพื้นที่ ส่งผลให้เหล่าผู้มาเยือนรู้สึกเสมือนกับได้พักหลบร้อนจากแสงอาทิตย์ภายในโอเอซิส

[©(c)Roland Halbe; Veroeffentlichung nur gegen Honorar, Urhebervermerk und Beleg / Copyrightpermission required for reproduction, Photocredit: Roland Halbe] [©(c)Roland Halbe; Veroeffentlichung nur gegen Honorar, Urhebervermerk und Beleg / Copyrightpermission required for reproduction, Photocredit: Roland Halbe]

โคมเรืองรองและแสงสว่างจากด้านบน

ในขณะที่สถาปนิกออกแบบ ‘ตัวกลาง’ ที่กั้นภายนอกออกจากภายใน ความสัมพันธ์ระหว่างงานสถาปัตยกรรม และแสงอาจปรากฏออกมาได้ทั้งจากภายในและภายนอก ที่ Maggie’s Centre Barts ศูนย์ดูแลผู้ป่วยมะเร็งในลอนดอน สถาปนิก Steven Holl หุ้มอาคารสามชั้นด้วยกระจกโปร่งแสงเนื้อด้าน ผิววัสดุสีขาวสว่างนวลถูกคั่นจังหวะด้วยแผ่นกระจกสี ด้วยหน้าตาที่ตรงข้ามกับบรรยากาศแนวสถานพยาบาลที่หลายคนอาจจินตนาการถึง เพราะสถาปนิกต้องการให้พื้นที่ภายในเป็นรูปเป็นร่างขึ้นด้วยแสงสีที่อาบพื้นและกำแพง บรรยากาศดังกล่าวยังแปรเปลี่ยนไป ตามแต่ละช่วงเวลาของวันและฤดูกาล ส่วนองค์ประกอบภายนอกนั้น เป็นผลจากการผสมผสานระหว่างการออกแบบแสงภายใน เอกลักษณ์อันเป็นเฉพาะของแสงจากกระจกโปร่งใสขาว และการออกแบบการวางตัวของแผงกระจกสีสันสดใสให้สอดคล้องกัน แล้วผลลัพธ์ที่ได้คืออะไร? คำตอบก็คืออาคารที่เป็นดั่งโคมเปล่งแสงอบอุ่นเรืองรอง ปรากฏกายอย่างโดดเด่นจากอาคารกำแพงหินที่ตั้งอยู่ภายในละแวกเดียวกัน โดยสถาปนิกหวังว่า การตั้งอยู่ของตัวอาคารจะสร้างความสดใสและเป็นเอกลักษณ์ให้กับมุมถนนของจัตุรัสอันงดงามของเมืองแห่งนี้

สถาปัตยกรรมของ Maggie’s Centre Barts แห่งนี้ บริหารจัดการแสงได้อย่างประสบความสำเร็จในแง่มุมที่มันสามารถสร้างบรรยากาศของพื้นที่ภายในและรูปลักษณ์ภายนอกที่แสดงท่าทีต้อนรับแก่ผู้มาเยือน ลักษณะอาคารอย่าง Maggie’s Centre Barts เรียกร้องการออกแบบแสงอย่างสร้างสรรค์ให้แสงแสดงออกทั้งสองฝั่งของ “ตัวกลาง” ในทางกลับกัน กับลักษณะของอาคารอย่างโบสถ์ การออกแบบ “ตัวกลาง” ต้องให้ความสำคัญกับพื้นที่ภายในเป็นอย่างมาก เนื่องจากผู้ใช้งานอาคารนั้น สื่อสารและครุ่นคิดอยู่กับความคิดของตนเอง แสงและสถาปัตยกรรมจึงมีบทบาทหน้าที่สำคัญในการบรรลุจุดมุ่งหมายนี้

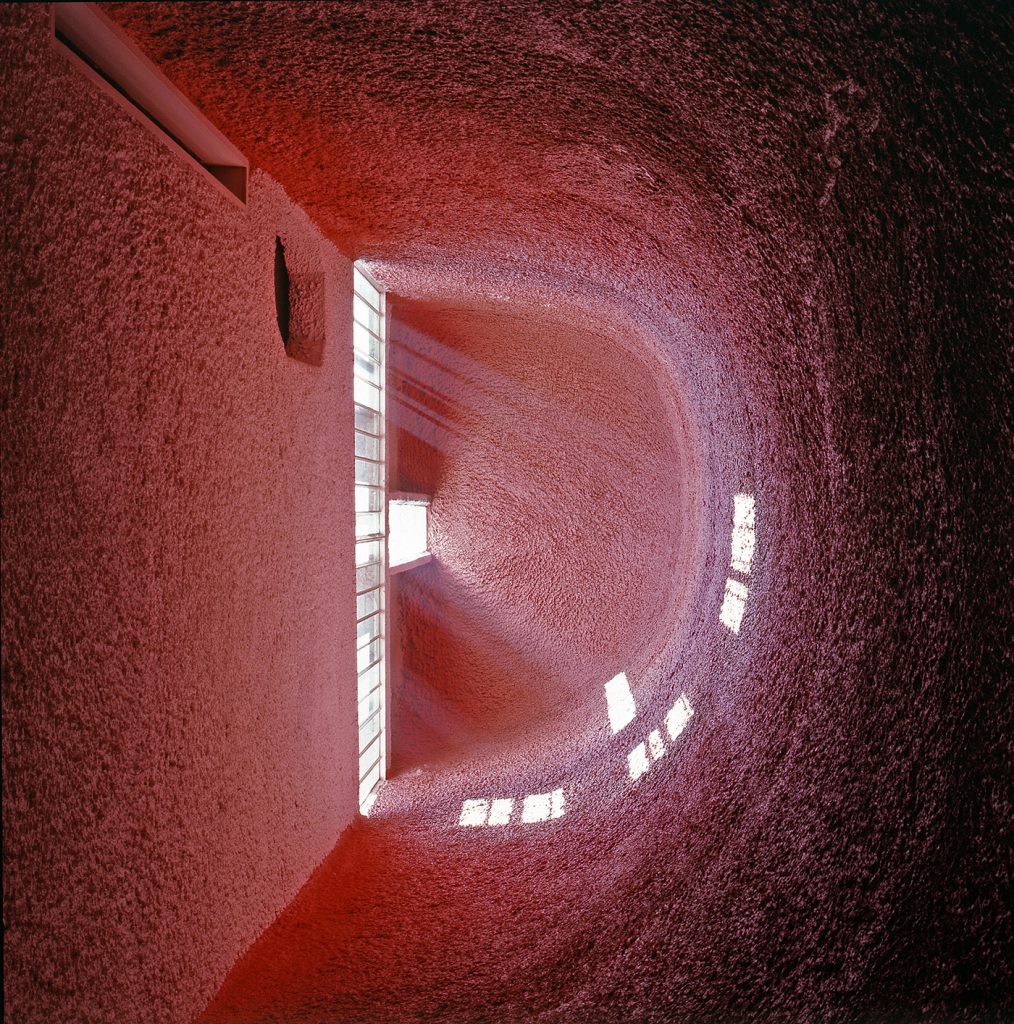

อาคารโบสถ์ Bagsværd ออกแบบโดย Jørn Utzon ตั้งอยู่ชานเมืองโคเปนเฮเกน ก่อร่างสร้างตัวมาจากความเข้าใจอย่างลึกซึ้งที่สถาปนิกมีต่อธรรมชาติของแสงอาทิตย์ภายในภูมิภาคและพื้นที่ที่งานตั้งอยู่ แสงอาทิตย์ในประเทศแถบสแกนดิเนเวียนนั้น นับว่าเป็นสิ่งที่หาได้ยากตลอดช่วงเวลาส่วนใหญ่ของปี ยกเว้นแค่เพียงในช่วงหน้าร้อน เส้นทางของดวงอาทิตย์เดินทางในระดับความสูงที่ต่ำตลอดทั้งปี และด้วยเหตุนี้เอง ด้านข้างของโบสถ์จึงมีหน้าต่างอยู่เพียงไม่กี่บาน โดยแสงจะได้รับอนุญาตให้เข้าสู่พื้นที่ภายในผ่านคอร์ทยาร์ด และช่องแสงบนเพดานที่วางตัวอยู่เหนือทางเดินยาวภายในที่กระจายไปยังส่วนต่างๆ ของอาคาร ส่วนที่โดดเด่นที่สุดนั้น แน่นอนว่าคือพื้นที่ใต้หลังคาโค้งในส่วนโถงพิธี เช่นเดียวกับส่วนของทางเดิน แสงถูกนำพาเข้ามาผ่านหน้าต่างช่องรับแสงที่ด้านบนของโบสถ์ ด้วยความช่วยเหลือจากพื้นผิวสีขาว ที่มีรายละเอียดของผิวสัมผัส ที่ปกคลุมพื้นผิวของที่ภายใน แสงถูกสะท้อน กระจายออก และทำให้มีความนุ่มนวลขึ้น เมื่อมันเดินทางไปถึงพื้นที่เบื้องล่าง บรรยากาศที่ได้คือความสงบนิ่ง อันอาจเป็นสิ่งที่ Henry Plummer เรียกว่า “ความเงียบที่เปี่ยมไปด้วยบรรยากาศ”

ขอแสงสว่างจงอย่าบังเกิด

ในการออกแบบ “ตัวกลาง” มันอาจจะเป็นประโยชน์มากกว่าที่เราจะตระหนักว่า แสงสามารถเข้ามาได้ในหลากหลายระดับแตกต่างกันไป ในหนังสือเล่มสำคัญอย่าง Towards a New Architecture ที่เขียนโดยสถาปนิกระดับตำนานของโลกอย่าง Le Corbusier ตอนหนึ่งของหนังสือเล่มนี้ Le Corbusier บรรยายการเดินทางผ่านมัสยิด Green Mosque แห่ง Broussaในดินแดนเอเชียไมเนอร์ หรือ อนาโตเลีย (ดินแดนทางตะวันตกเฉียงใต้ของทวีปเอเชีย) ลำดับของพื้นที่เริ่มขึ้นจากประตูทางเข้าเล็กๆ ตามมาด้วยบริเวณที่พื้นผิวปกคลุมไปด้วยหินอ่อนขาวและแสงสว่างสดใส พื้นที่ข้างๆ ปรากฏอยู่ในขนาดเดียวกัน แต่ถูกยกขึ้นให้วางตัวเหนือขั้นบันได และอยู่ภายใต้ความเข้มข้นของแสงที่น้อยกว่าพื้นที่อีกด้าน ขนาบข้างพื้นที่นี้ คือพื้นที่อีกส่วนหนึ่งที่มีขนาดเล็กกว่า และมีปริมาณของแสงที่อ่อนกว่า ท้ายสุดแล้ว การเดินทางผ่านอาคารนี้ จบลงที่พื้นที่ขนาดเล็กที่อยู่ใต้ร่มเงา จากข้อเขียนของ Le Corbusier เราสามารถสรุปความได้ว่า ความหลากหลายของแสงและปริมาตร ที่เกี่ยวพันกับสัดส่วนมนุษย์ และวัสดุที่เลือกใช้ ได้สร้างสิ่งที่เขาเรียกว่า “จังหวะ” หรือ ‘the rhythm’ ขึ้นมา ในบางพื้นที่ แสงสว่างอาจเกิดขึ้น และในพื้นที่ที่เหมาะสม แสงสว่างก็อาจจะเกิดขึ้นในปริมาณที่น้อยลง

ชีวิตจงเกิด

แสงอาจถูกกระจายออก กระพริบ ส่องประกาย ปรากฏเป็นจุดระยิบระยับ เรืองรอง หรือมีความอ่อนละมุนลง และอื่นๆ ผลงานออกแบบที่กล่าวมาข้างต้นของการใช้ “ตัวกลาง” เป็นเพียงตัวอย่างเพียงไม่กี่ตัวอย่างเท่านั้น สิ่งที่จะเกิดตามมาขึ้นอยู่กับจินตนาการของนักออกแบบในการที่จะรังสรรค์ “ตัวกลาง” โดยมีธรรมชาติของแสงอยู่ในห้วงคำนึง เพิ่มชีวิตชีวาให้กับพื้นที่ และก้าวข้ามผ่านสภาวะของการคงอยู่ อย่างไร้ซึ่งความเคลื่อนไหวของอาคารสิ่งก่อสร้าง หรือดังที่ Henry Plummer กล่าวไว้ในคำนำของการศึกษาแสงของเขาว่า “สำหรับใครก็ตามที่มองหาหนทางที่จะสร้างพื้นที่ ที่อยู่เหนือการมีอยู่ทางกายภาพ”

These first four verses begin the first chapter of the Book of Genesis in the Holy Bible, detailing how God created the world, and thus, humanity. Let there be light shows the power of God, that once he commanded, it happened as he desired. But if we read Let there be light within the context of the opening verses, we may get an extra clue on our perception of ‘light’. Formless, obscure, and immoral, light gives rise to the opposite—clarity, virtue, and most importantly, life.

In 2016, the Daylight Award was founded to award architects, designers, scientists, or researchers who contribute to the research or design of daylight on human health, the quality of life and the value to our society. From the Book of Genesis till today, light still maintains our perception of being virtuous, linking with life and our well-being. But what is it about light in architecture that architects are so fascinated by that a prestigious award was established just for it?

The Dead comes to Life

Specifically for 2020, a special prize, namely the Lifetime Achievement Award was added to the Daylight Award. Henry Plummer, a professor in architectural history and an architecture photography enthusiast, won this inaugural award. In his research, Plummer argues that buildings are static. ‘Deadened volumes’ as Plummer terms, show signs of life, not only as people populate it, but once beams of light ‘pierce into rooms or glide over walls’. In other words, architecture only changes, moves, and comes alive once natural light is added to the mix.

Let’s step away from architecture into art for a moment to explore how building comes alive. Thai National Artist Preecha Thaothong is best known for portraying temples under the effect of sunlight. A temple is brightly lit by sunlight, framed by another building element in dark shadow. An architectural element lying off the canvas casts its shadows onto a mural, contrasting with another part of the same mural brightly lit by sunlight. Varying depths of the building are emphasised as some volumes stand out under sunlight and other recede under the influence of shadows. Temples bathe in the yellow-tinted light of the morning or glows against the dark blue sky at twilight. As captured in these frozen pictures as though time stands still, architecture or ‘mute objects’ as Plummer calls, changes in response to the hour of the day thanks to sunlight. In his practice, Thaothong articulates that light travels infinitely unless another ‘medium’ blocks its route. So as a designer, what are the ways to design the ‘medium’ to create such interplay?

The Blocks

Arguably, transparency is one of the most preoccupied topics in the history of architecture. Since ancient civilisations, we often strive to puncture solid walls and bring natural light to the interior. The breakthrough was during the modernist movement with the recurring images of floor-to-ceiling windows and the sleek interior flooded with natural light. But covering the sides of the building with large panes of glass is not the singular way to design the ‘medium’ for this era. In 1932, Pierre Chareau and Bernard Bijvoet cladded a three-storey house in Paris with translucent glass blocks. Maison de Verre, literally translated as a house of glass, contains an airy double-height lounge lit with diffuse sunlight. This seems common now, but how different and pioneering it must have felt in the 1930s. And how timeless this quality of light is in domestic architecture even today.

Eighty years later in Tokyo, a façade of brick-sized glass blocks is employed in Optical Glass House by Hiroshi Nakamura & NAP. Located next to a busy road, the challenge is to shut out sound while bringing in views and natural light. Behind the façade of 8.6×8.6 metres is a garden of ash, maple, and holly trees. The architect’s statement describes the various results of light produced by the combination of glass blocks and trees. Among them are scattered, filtered light; shimmering courtyard; dancing patterns of light and shadow on the floor. Further interplay between light and architecture is achieved as the architect places a water basin-cum-skylight right above the entrance. Here the power of light combines with water and projects flickering light patterns on the floor, greeting visitors or informing residents leaving home on the climate of the day. Whether the water is still, gently moved by the wind, or pitter-pattered from the rain; the light pattern follows. The architect designs the ‘medium’ to allow residents to live in awareness of the changing season via the changing daylight.

The Filter

Natural light is inherently desirable to building users. But in a climate where the sun is extreme, what are the ways to design the ‘medium’? Perforated screens, often known as Jali in India, or Mashrabiyya in the Middle East, are vernacular elements that help cut down the sun, thus the heat and the glare that comes with it. The ornately carved geometric patterns are not purely aesthetics, but are an effective means for ventilation, too.

Perhaps Jean Nouvel gives a contemporary interpretation of this age-old knowledge. At the Louvre Abu Dhabi, natural light is filtered through layers of complex stainless steel and aluminium latticework and dapples the floor of the museum. Behind this outcome is a 180-metre-wide perforated dome hovering above as if an enormous Jali screen has been turned from wall to ceiling. The result is magical, celestial, and rooted to the place as though visitors take shelter from the sun in an oasis.

The Glowing Lantern and the Light from Above

As an architect designs the ‘medium’ between the interior and exterior, the relationship between architecture and light could manifest both from within and on the outside. At Maggie’s Barts, a support centre for cancer patients in London, Steven Holl wraps the three-storey building with translucent matte glass. The luminous white skin is punctuated by colourful glass panels. Contrasting to the clinical atmosphere that one might picture in a cancer support centre, Holl wishes the interior to be shaped by coloured light washing the floors and walls. This atmosphere shall also change by the time of day and season. Externally, it is a combined effect between the interior lighting that Holl specifically design with the effect of the translucent white glass and the positioning of the colourful panels. The result? A warm glowing lantern. It stands out from the rest of the neighbouring stone-cladded buildings and Holl hopes it would provide a ‘joyful, glowing presence on this corner of the great square’

Maggie’s Centre at Barts successfully manages light in a way that creates a pleasant interior atmosphere and manifests a welcoming gesture on the exterior. Both sides of the ‘medium’ call for creative use of light. Meanwhile, for a different building typology like churches, a focus on its interior is required as visitors meditate with their thoughts. Light and architecture play an important role in achieving this goal. Jørn Utzon’s Bagsværd Church on the outskirts of Copenhagen derives from his profound understanding of the nature of sunlight in the region. Sunlight in Scandinavia is scarce for most of the year except during summer. The path of the sun travels at low altitudes for the whole year. For this reason, the sides of the Church contain a very limited number of windows. Light is admitted, instead, via courtyards and skylights that covers the long corridors transversing the building. The most distinctive feature is undoubtedly the rolling vaults in the sanctuary. Like the corridors, light is admitted from above via clerestory windows. With the help of the white textured surfaces covering the interior, light is reflected, diffused, and softened as it reaches the space below. The resulting atmosphere is serene. And perhaps what Henry Plummer may call ‘atmospheric silence’

Let there be no light

In designing the ‘medium’, it might be useful to remember that light comes in varying degrees. In the iconic Towards a New Architecture by Le Corbusier, the world-renowned architect describes a journey through the Green Mosque in Broussa in Asia Minor. The sequence begins with a small doorway, followed by a great white marble-cladded space filled with light. An adjacent space repeats the same size but is raised on many steps, with half the light intensity of the previous. Flanking this space is the space smaller in size, with the light subdued. Culminating the narration are two smaller spaces in shade. From Le Corbusier’s notes, we can conclude that it is the varying light and volume, in relation to our human scale and chosen materials that produce what the architect calls ‘the rhythm’. Perhaps, there shall be light. And where appropriate, there shall also be less light.

LET THERE BE LIFE Light could be diffuse, flickering, shimmering, dappling, glowing, softened, subdued, and so on. The aforementioned designs of the ‘medium’ are merely few examples. What’s next is up to the designers’ imagination to create the ‘medium’ with the nature of light in mind, adding life to space, and going beyond the seemingly static building—or as Henry Plummer puts it in an introduction to his study on light: ‘For all those seeking to create space that transcends the physical.